August 2000

from OrderOfTheTwilightStar Website

.

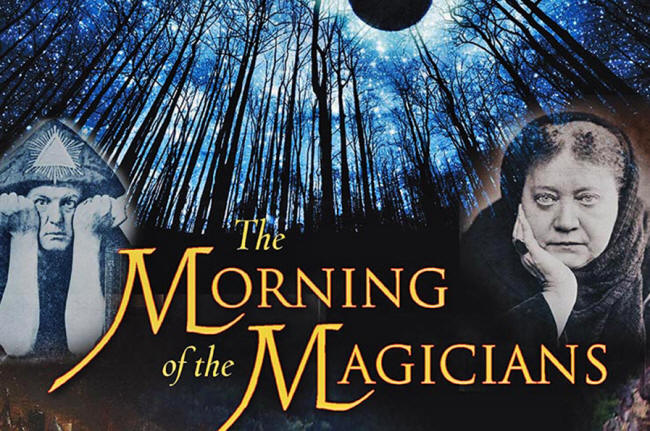

| This essay was written over 10 years ago, and reflects the state of my knowledge and opinions at the time. A good deal has changed since then, including the death of Louis Pauwels in 1997. The reader may well be thankful that I have chosen not to revise and expand this essay or it’s dark companion. Above, the marvelously trippy cover of the 1968 Avon paperback edition of Morning of the Magicians. |

There is only one work, that I know of, that contains almost all of the themes that typify the fantastic and visionary ideals now associated with the 60’s and 70’s. And it does so with such an amazing percussive force that the work takes on an uncanny prophetic aura, when it is read today.

The book, Le Matin des Magiciens, appeared in Paris, in 1960. A translation, by Rollo May, was published in Britain, in 1963, under the title The Dawn of Magic, and made its way to the US a year later as The Morning of the Magicians.

[I will refer to the book by its US title or abbreviation MOTM]

The authors were esoteric writer Louis Pauwels, and physicist Jacques Bergier. The book was written as a kind of manifesto for “fantastic realism” and was meant to evoke, or harken back to, the spirit of the surrealistic manifestos of the 1920’s.

From Sept/Oct 1964 The title was quite successful in France, creating controversy and discussion within Gallic intellectual circles. Pauwels and Bergier founded a periodical Planete to continue the work begun with Morning of the Magicians.

According to Mircea Eliade in Occultism, Witchcraft and Cultural Fashions (1976 entry), Planete had 80, 000 subscribers and 100,000 buyers, which was amazing because the journal was expensive. They followed MOTM with Impossible Possibilities in 1968 and The Eternal Man in the 70’s.

Bergier continued to publish titles, mostly on the subject of UFOs and “extraterrestrial genesis” throughout the 70’s. MOTM is usually remembered today for one section entitled “A Few Years in the Absolute Elsewhere,” which deals with Nazi “fringe” and occult ideas (And the obvious inspiration for my title for this bibliography).

It is also remembered, with ambiguous feelings, for first presenting the germ of the “extraterrestrial genesis” thesis, later exploited to extremes by Robert Charroux and Erich von Daniken.

MOTM is unique from the beginning. The book opens with an extremely personal preface from Louis Pauwels:

“Physically I am a clumsy person and I deplore the fact.”

With this opening, suited more for a personal confession or autobiography, Pauwels sets a personal tone for the work that remains throughout.

This aspect of MOTM can be easily overlooked in the onrush of ideas which follows. MOTM is a personal work, on the evolution of their ideas of the dynamics of life on earth.

The structure of the books is really based on an evolutionary dialectic, rather than traditional logical arguments. This allows the book to move through a vast amount of material, often pitting one anomalistic event or fact against another, aiming toward a new synthesis within the reader.

For this reason the book is very difficult to summarize or review in an objective manner. It does not hammer home an argument, as is the usual case, but is constantly moving towards an argument.

Pauwels writes that MOTM is the result of,

“five years of questing, through all regions of consciousness, to the frontiers of science and tradition. I flung myself into this enterprise — and, without adequate equipment– because I could no longer deny this world of ours and its future, to which I so clearly belong.”

Pauwels then chronicles his search, which takes him from the existential malaise of current intellectualism, through his involvement with Hinduism and Gurdjieff, to a new excitement.

Here, as the perceptive Jim Hougan noticed in Decadence, is one of the hallmarks of the early “counterculture” – a rejection of pessimism, and a belief that change and evolution will bring something positive and superior. The difference between this new idea and traditional 19th century “progressivism” is that new thought (or heresy) suggests that evolutionary process can be accelerated.

Pauwels tells how he and Bergier embarked on five years of study to arrive,

…at a point of view which I believe is rich in its possibilities. This is how the surrealists worked thirty years ago. But unlike them we were exploring not the regions of sleep and the subconscious but their very opposites: We call our point of view fantastic realism.

Pauwels’ choice of words “ultra-consciousness” and “awakened state” are well worth noticing as he will return to these ideas, again and again.

Fantastic realism, according to Pauwels, has nothing to do with the bizarre, the exotic, the merely picturesque. There was no attempt on our part to escape the times in which we live.

We are not interested in the “outer suburbs” of reality: on the contrary we have tried to take up a position at its hub. There alone we believe, is the fantastic to be discovered – and not a fantastic leading to escapism but rather to a deeper participation in life.

So, Pauwels explains, asking the reader to look at reality with new eyes or to be accurate, with “awakened eyes.”

I think that Pauwels’ involvement with Gurdjieff is showing itself. Pauwels is best known, outside of France, for a book he wrote criticizing the Gurdjieff circle.

Pauwels continues his criticism of Gurdjieff in MOTM, but it is obvious to me that he has accepted the central Gurdjieffian notion that man is asleep, and must be shocked into an awakened state in order to perceive true reality. Gurdjieff’s ideas and doctrines loom large in MOTM, and he is one of the first personalities mentioned in the work.

This is perhaps the best time to mention one of the uncanny aspects of Morning of the Magicians.

Any prominent mention in its pages seems to guarantee a revival of some significance in the 60’s and 70’s. This is especially true when it comes to some of the writers singled out for discussions in MOTM. Many of them were totally forgotten in 1960. For example, I suspect that MOTM had a large part in the rediscovery of G. I. Gurdjieff.

Morning of the Magicians is divided into three parts. Part One, almost the first half of the book, is subdivided into four long sections, “The Future Perfect,” “The Open Conspiracy,” “The Example of Alchemy,” and “Vanished Civilizations.”

It has much in common with books by Charles Fort and his later imitators. During the 50’s, writers like Frank Edwards had taken up the mantle of Charles Fort and had begun producing books on anomalistic, unexpected, and impossible events, which defied logical scientific explanation.

Edwards’ Stranger than Science (1959 entry) is a good example of these popular titles, which told about steel nails found in rocks, spontaneous human combustion, and strange things falling from the skies. Most of them were made up of many short chapters, suitable for reading in the bathroom, written in breathlessly sensational rhetoric.

Many of these books were little more than catalogues of bizarre events. Pauwels and Bergier were familiar with this genre and certainly exploited their readers expectations.

- Part One of MOTM is no catalogue of the curious and unexplained. There is a calculated dialectic at work. In this, Pauwels and Bergier are more indebted to the father of the study of anomalies, Charles Fort, than they are to his somewhat uninspired imitators. Fort is the subject of a whole chapter in Part One, and it is obvious that his writings have had great impact on the authors, and upon the structure of MOTM. Pauwels had “instigated” the first translation of Fort’s The Book of the Damned (1917) in a French edition in 1955. And I suggest that Fort’s quixotic dialectic used throughout the book forms the central mode of argument of MOTM. Martin Gardner had pointed out, in Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science(1957), that “Fort was an Hegelian. In the last analysis, existence–not the universe we observe but everything that is–is a unity. There is an ’underlying oneness’ and ’inter-continuous nexus’ which holds everything… Fort was not a religious man, but he granted that the totality of things might be an organism with intelligence.” Thus, each anomalous fact recorded in MOTM is no bizarre tidbit to tweak our fancy, but part of a careful dialectical progression.

- Part Two, “A Few Years in the Absolute Elsewhere,” follows hard upon these four “Fortean” essays. To be properly understood, it must be taken as part of the dialectic set up in Part One. For this reason, “A Few Years in the Absolute Elsewhere” is the most misunderstood part of MOTM. It is not an expose of crack-pot science, of the satanic influences on Hitler, or of the occult origins of Nazism. The essay is really about how we view history. One of Pauwels’ themes is that the people of ancient civilizations are really alien to us–as alien as creatures from another planet. Their plunge into the dark corners of physical Nazism is an object lesson in recent history. Here are people who came from the same European intellectual and cultural traditions as you and I, but they appear in hindsight to be totally alien–as though they were from another planet, or an “absolute elsewhere.” Far from being a catalogue of Nazi weirdness, it is a long antithesis to the thesis that says that because the Nazis were a recent phenomenon, we understand them better.

- Part Three, “That Infinity Called Man,” consists of ten chapters, each of which has its own title. [That each part is organized along different lines, suggests that ex-Gurdjieffite Pauwels may have had musical forms in mind as a structure.] Much of Part Three are long quotes, or synopsis blocks, placed in juxtaposition to each other, to illustrate the problems of man’s future potential. Finally, Pauwels and Bergier arrive at the final chapter entitled “Some Reflections on the Mutants,” and the idea that mankind is already at the point where it is mutating into a “perfected man,” perhaps in the “awakened state.” This is not new idea. Neitzsche also postulated such a “new man” (also through use of the dialectic), and Hitler forever stigmatized it with negative meanings when he took Neitzsche literally (always a mistake). To speculate about things in post-war France must have taken more than the usual amount of guts.

I have tried to cover some of the main points of Morning of the Magicians because they are often overlooked within the rich field of secondary information and digressions that abound throughout the work.

MOTM was both blessed and cursed by being full of tantalizing mysteries and enigmas, with enough throw-away ideas to inspire a library of speculation. In terms of MOTM’s long term influence, the marginal information often came to outweigh the authors’ original intent. It is important to look at some of that material.

One of the first concepts that the authors explore is the idea of an “open conspiracy” to change society in a positive way. The term comes from a book written by H. G. Wells in his later years. Wells thought it was time (1928) for small groups to engage in an “open conspiracy” to bring about positive global change. Naturally, Wells saw the “open conspiracy” as being stimulated by the best scientific brains of the day. Pauwels and Bergier then tell of several examples of such an “open conspiracy” in the past.

The first example is that of the Rosecrucians of the 17th century and their mysterious manifestos. These claimed to be from a secret brotherhood of men who sought to unify Europe along ideological and mystical lines.

The authors wonder if the Rosecrucians might be the model for a modern,

“…secret international society of men of the highest intelligence, spiritually transformed by the profundity of their knowledge…”

The authors think the answer is “yes.” They write,

“…we have every reason to believe that a society of this nature is being formed today by the pressure of events, and that there is bound to be one in the future.”

The second example of an “open conspiracy” cited is that of the “nine unknown men” who are reputed to watch over the destiny of India (maybe the world).

The version of the “nine unknown” used in MOTM is from Talbot Mundy’s novel The Nine Unknown.

Pauwels and Bergier use fiction throughout the work. Fiction writers have always had a gift for seeing through the veil of reality, and MOTM makes great use of these fictional visions. Mundy is a good choice, as his own mystical vision is close to those of the authors.

There is a long excerpt from a John Buchan tale, The Power House, in which the hero has an unnerving conversation with a conspirator in a group of “extra-social intelligences” — idealists who are going to make a new world. The story is from 1910, and the ideas expressed sound uncomfortably like Nazism.

[Buchan is best known as the father of the modern spy novel, but was a loyal servant of the late British Empire, serving as Governor General of Canada for a while. He expressed some of the same fear of new fascist groups in his The Three Hostages, 1924.]

Pauwels and Bergier call this “rule by cryptology.”

These early thoughts predate the esoteric conspiracy theories popular in the 60’s and 70’s. The conspiratorial view of history was common in France, and the authors may have been following some ideas current at the time. There isn’t any doubt that MOTM is source for much of the material used by Shea and Wilson in The Illuminatus! Trilogy.

I think it is also an inspiration for the W.A.S.T.E. conspiracy in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. MOTM may also be a factor in the sudden revival of Talbot Mundy’s novels in the 60’s. Later, Marilyn Ferguson would list MOTM among her precursor in The Aquarian Conspiracy, which is an unabashed call for an “open conspiracy” along New Age lines.

One of the most important sections in Morning of the Magicians is the speculation on a possible connection between the ancient art of alchemy and modern atomic physics. Pauwels and Bergier suggest that some of the practitioners of alchemy may have understood the nature of matter, and wrote about it in their special symbolic language.

I’m sure that this is one of Pauwels and Bergier’s contributions to the literature of the 60’s and 70’s. Alchemy became one of the “buzz words” in certain intellectual circles, during this period. New surveys were written on alchemy, and the classic studies were reprinted.

It is well known that Morning of the Magicians inspired a whole genre of “mysteries of ancient civilization” titles. The germ for most of them can be found in “Vanished Civilizations,” in Part One. It’s all here, from the Piri Reis map to pyramidology.

The authors are frankly fascinated by the idea that ancient peoples may have been more advanced in some of their technologies than we generally believe.

“Anthropology is awaiting its Copernicus,” they declare.

Many of us who have studied in the discipline would tend to agree.

But this fascination with possibilities does not lead them too far from reality. “We must avoid falling into the trap of paying too much attention to legends,” they caution. The speculation on “advanced wisdom of the ancients” was already a topic of French fringe literature before Pauwels and Bergier came along. They just seem to have reshaped it, and given it a more concrete direction.

The authors may be responsible for creating interest in Arthur Machen, and his biggest fan, H.P.Lovecraft.

Like Talbot Mundy, Machen and Lovecraft were writers from the pre-war age who were in eclipse in the 50’s. In 1945, that ultimate snob of American letters, Edmund Wilson, had declared Lovecraft, and by implication most “genre fiction,” to be “hack work.” It is also likely that MOTM and Colin Wilson’s The Strength to Dream are responsible for the revival of Lovecraft in the mid 60’s.

MOTM sings the praises of Arthur Machen, calling him a “neglected genius,” and rightly identifying him as a member of the Order of the Golden Dawn. It is really the Golden Dawn that interests Pauwels and Bergier, and Machen allows them a literary entrance to the discussion of that brand of occultism. I think it quite unlikely that Machen would have been rediscovered in the late 60s had not Pawels and Bergier shown a light on his work.

Pauwels and Bergier’s discussion of the Golden Dawn is one of the most curious passages in MOTM.

The discussion of Machen and the Golden Dawn falls in “A Few Years in the Absolute Elsewhere,” which is concerned with Nazism. According to the authors, the Golden Dawn,

“…was in contact with similar German society, some of whose members were later associated with Rudolf Steiner’s famous Anthroposophical movement and other influential sects during the pre-Nazi period.”

Then a few pages later they write,

“This neo-pagan society… was an offshoot of the English Rosecrucian Society, founded by Wentworth Little in 1967. Little was in contact with German Rosecrucians.”

They then go on to connect Rosecrucian Bulwer-Lytton’s novel The Coming Race with the proto-Nazi Vril Society. The Coming Race is about a race of men who have become “supermen.” According to the authors,

- the “nine unknown” of India

- the mahatmas of Theosophy

- the “secret chiefs” of the Golden Dawn

- the “new man” of Hitler…

…are all chips off the same block.

Here the reader is at the birth of a persistent modern “myth”: That Nazism is the product of occult doctrine. To be fair, the authors were not saying that the Order of the Golden Dawn was a proto-Nazi group. Nor were they suggesting a positive link.

“Looking for affiliations is a game, like looking for ’influences’ in literature,” they warn. “When the game is over, the problem is still there.”

This hasn’t stopped writers who followed from trying to make affiliations stick. None of them have been able to come up with much evidence that would convince an exacting historian.

The final part of Morning of the Magicians deals with the idea of the “perfected man.” This theme weaves its way through the work, and would come to intrigue a whole generation of writers from Colin Wilson to Marilyn Ferguson. The tool for perfecting man is the brain. There is little doubt among most of the later writers about this. It is a persistent theme of MOTM that some so-called magicians and alchemists may have actually been seeking the “perfected man,” or the state of perfection, and that their writings may offer clues to modern man.

This is why MOTM deals in such great lengths with “open conspiracies,” Rosecrucians, and secret societies. These groups all claimed some clue to the perfection of man–even had planned agendas. Even the book’s long digression on Nazi Germany is really a look at an “open conspiracy” that went horribly wrong. Eventually, all of MOTM’s special topics amplify these speculations about the “perfected man.”

All this sounds very similar to Colin Wilson’s “faculty X” theory of a decade later. Wilson would search the annals of the mystical and the occult with the suspicion adepts had experimented with “man’s untapped potential,” which he called “faculty X.” Wilson’s highly influential The Occult covers a lot of the same ground that MOTM covers, but in a more structured and detailed way. If Pauwels and Bergier had any inspiration for Wilson, then they were truly influential beyond a limited circle of occult readers.

In the next 20 years, this theme of the “perfected man,” with different names, would run through a whole sub-strata of literature, from serious studies in the paranormal to the “human potential” pundits, to the silliest of self-books. In a way, it is here that MOTM saw its greatest impact. The oblique call for an “open conspiracy” was heeded.

Before leaving this discussion of Morning of the Magicians, a few other observations should be made. First, I must complain about the lack of information about Pauwels, Bergier, Planete, or on “fantastic realism” in English. Maybe some social historian with a background in French cultural and political trends might take the bait, and lift the veil of obscurity from this subject. The following example may illustrate the problem. In 1965, Mircea Eliade mentioned the success of Planete in a lecture given at the University of Chicago.

He noted that MOTM

“…has not made a considerable impact on the Anglo-American public,” which suggests that MOTM’s impact in the US may have come with the paperback edition.

But then Eliade says,

“In 1961, they published a voluminous book, Le Matin des Sorciers…” [Reprinted in his Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashion]

All the facts in that statement are wrong. It was published in 1960, the title was Le Matin des Magiciens, and was a volume of rather average length! Eliade’s major sources seemed to have been two unspecified articles in Le Monde. Gaffs like that, from highly respected scholars, tended to be repeated as fact, for decades.

It is obvious that the dominant personality in the team is Louis Pauwels. In some works, which cite MOTM, the work is considered Pauwels’ work alone! It is his style and personal voice which drives the book’s engines. When comparing MOTM with later books by the team, this fact becomes clearer. Impossible Possibilities (1968, 1971, and 1973 entries) is a series of essays, each signed by each of the authors.

Following two opening essays by Pauwels, the bulk of the text is by Bergier. Bergier comes up clearly prosaic in comparison. The Eternal Man (1972 and 1973) is also a series of essays, this time unsigned, but the noticeable uneven quality betrays that much the same is going on. Bergier without Pauwels is much less exciting.

Bergier is the scientist fascinated by all sorts of fringe material, from UFO’s to the “advanced technologies” of ancient civilizations. It is Bergier who is most excited by the theories of extraterrestrial genesis. One can see how the team must have worked.

It was surely Bergier who collected the examples of Nazi fringe science, while Pauwels collected information on the esoteric connections with Nazism. But the later books lack the cohesive vision so dynamic in Morning of the Magicians. I can only assume that cohesive vision came from Louis Pauwels.

Pauwels worked for the conservative Le Figaro, and from vague hints, I assume him to be a figure of the French right.

Peter Partner, in Murdered Magicians, described him, for English readers, as an anti-Catholic G. K. Chesterton! Partner also suggested that he began to distance himself from some of his earlier writings, in the early 80’s.

Pauwels’ views, as articulated in MOTM. would not be welcome in the mainstream of the American right in the 80’s, while libertarian and objectivist circles might enjoy them.

There is some evidence that the popularity of MOTM caught the authors by surprise. Pauwels said as much in Impossible Possibilities.

“The impact of the book, we thought, would be more one of depth than one of numbers–hopefully shaking its readers to the very core. We simply could not imagine that it would attract the general public,” he wrote.

MOTM was written with a more esoteric audience in mind.

Whatever limited audience the authors of MOTM envisioned for their work, the ideas caught the imaginations of readers on two continents.

It would be easy to dismiss Morning of the Magicians as an artifact–a dated piece of late 50’s fringe literature which managed to attract some notoriety. To do so would be to ignore the totality of the work’s subject matter. That is the reason that I have suggested it to be treated as a manifesto for much of the esoteric intellectual interests of the 60’s and the 70’s. Pauwels and Bergier were willing to ask questions–not just prosaic ones, either–but outrageous questions.

Their dialectic suggested a whole range of outrageous and exciting solutions to these questions. This excitement and its quixotic spirit gave it appeal to an emerging generation that came to value these qualities highly. Even today, it still retains a peculiar ability to stimulate creative contemplation, and it is still fun to read.

It would not surprise me if a new edition should appear soon to challenge a new generation.

![]()

by Terry Melanson

from ConspiracyArchive Website

The Vril Society or The Luminous Lodge combined the political ideals of the Order of the Illuminati with Hindu mysticism, Theosophy and the Cabbala.

It was the first German nationalist groups to use the symbol of the swastika as an emblem linking Eastern and Western occultism.

The Vril Society presented the idea of a subterranean matriarchal, socialist utopia ruled by superior beings who had mastered the mysterious energy called the Vril Force.

“This secret society was founded, literally, on Bulwer Lytton’s novel

The Coming Race(1871). The book describes a race of men psychically far in advance of our own.

They have acquired powers over themselves and over things that made them almost godlike. For the moment they are in hiding. They are said to live in caves in the center of the Earth. Soon they will emerge to reign over us.”

While researching their classic book, Morning of the Magicians, authors Jacques Bergier and Louis Pauwels were given the above account by one of the world’s greatest rocket experts, Dr. Willy Ley, who fled Germany in 1933.

Dr. Ley said that the Vril Society – which formed shortly before the Nazis came to power – believed they had secret knowledge that would enable them to change their race and become equals of the men hidden in the bowels of the Earth. Methods of concentration, a whole system of internal gymnastics by which they would be transformed.

These methods of concentration were probably based on Ignatius Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises.

The Jesuit techniques of concentration and visualization are similar to many occult teachings, especially in shamanic cults and Tibetan Buddhism. The Nazi’s revered these Jesuit Spiritual Exercises, which they believed had been handed down from ancient Masters of Atlantis.

The occultists of the time knew that Ignatius was a Basque – some claimed that the Basque people were the last remnant of the Atlantean race – and the proper use of these techniques would enable the reactivation of the Vril for the dominance of the Teutonic race over all others.

The Vril Society believed that whoever becomes master of the Vril will be the master of himself, of others around him and of the world. The belief was that the world will change and the “Lords” will emerge from the center of the Earth. Unless we have made an alliance with them and become “Lords” ourselves, we shall find ourselves among the slaves, on the dung-heap that will nourish the roots of the New Cities that will arise.

In The Unknown Hitler, Wulf Schwarzwaller says:

“In Berlin, Haushofer had founded the Luminous Lodge or the Vril Society. The Lodge’s objective was to explore the origins of the Aryan race and to perform exercises in concentration to awaken the forces of “Vril”.

Haushofer was a student of the Russian magician and metaphysician George Gurdjieff. Both Gurdjieff and Haushofer maintained that they had contacts with secret Tibetan lodges that possessed the secret of the “Superman.” The Lodge included Hitler, Aalfred, Rosenberg, Himmler, Goring and Hitler’s subsequent personal physician Dr. Morell.

It is also known that

Aleister Crowleyand Gurdjieff sought contact with Hitler. Hitler’s unusual powers of suggestion become more understandable if one keeps in mind that he had access to the “secret” psychological techniques ofGurdjieffwhich, in turn, were based on the teachings of the Sufis and the Tibetan lamas and familiarized him with the Zen teaching of the Japanese Society of the Green Dragon.”

The Vril Force and the Black Sun

In Lytton’s The Coming Race, the subterranean people use the Vril Force to operate and govern the world (a few children armed with vril-powered rods are said capable of exterminating a race of over 22 million threatening barbarians).

Served by robots and able to fly on vril-powered wings, the vegetarian Vril-ya are – by their own reckoning – racially and culturally superior to everyone else on Earth, above or below the ground.

At one point the narrator concludes (from linguistic evidence) that the Vril-ya are

“descended from the same ancestors as the great Aryan family, from which in varied streams has flowed the dominant civilization of the world.”

The Vril Force or Vril Energy was said to be derived from the Black Sun, a big ball of “Prima Materia” which supposedly exists in the center of the Earth, giving light to the Vril-ya and putting out radiation in the form of Vril.

The Vril Society believed that Aryans were the actual biological ancestors of the Black Sun.

This force was known to the ancients under many names, and it has been called Chi, Ojas, Vril, Astral Light, Odic Forces and Orgone.

In a discussion of the 28th degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry – called Knight of the Sun or Prince Adept – Albert Pike said, “There is in nature one most potent force, by means whereof a single man, who could possess himself of it, and should know how to direct it, could revolutionize and change the face of the world.”

This is the force that the Nazis and their inner occult circle were so desperately trying to unleash upon the world, for which the Vril Society had apparently groomed Hitler. A manifestation of the “Great Work” promulgated by the Adepts of secret societies throughout the ages.

The Vril Society latched on to a very old archetype already in the minds of alchemists and magicians, which was only re-interpreted, by Lytton, in light of that age of occult revival and scientific progress.

The idea of mutation and transformation into a higher form of a “god-man” was envisioned, through the Vril-ya, in Buller-Lytton’s The Coming Race.

Lytton, himself, was an initiate of the Rosicrucians and was well versed in the arcane-esoteric philosophies (and of course the greatest advances in the sciences of his day).

“Through his romantic works of fiction he expressed the conviction that there are beings endowed with superhuman powers. These beings will supplant us and bring about a formidable mutation in the elect of the human race.”

(J. Bergier)

This is where the philosophy turns dangerous.

The moment we speak of an elect and “illumined” class which is above the general populace, you inevitably encounter racism and classism – with fascism in due course.

“We must beware of this notion of a mutation,” Bergier warns. “It crops up again with Hitler, and is not extinct today.”

Bergier and Pauwels were writing in 1960, but today this philosophy is, sadly, once again in the forefront of popular culture.

The New World Order, so vehemently opposed, is under the direct influence and guidance of the New Age Movement. A hodgepodge of occult doctrines and dangerous socialism, which hides under a cover of “spiritual enlightenment.” Theosophy is considered the main foundation, and its founder, Mme. Blavatsky, was a great admirer of Lytton’s.

In The Occult Conspiracy, the excellent researcher, Michael Howard, writes about the compatibility of the two philosophies:

“Blavatsky had read Bulwer Lytton’s novels and was very impressed by their occult content, especiallyZanoniand theLast Days of Pompeii. The latter was published in 1834 and dealt with the time between early Christianity and the Mysteries of Isis in Italy in the first century A.D.

Blavatsky’s esotericism was virulently anti-Christian…

The racial ideas of Madame Blavatsky, concerning root races and the emergence of a spiritually-developed type of human being in the Aquarian Age, were avidly accepted by the nineteenth-century German nationalists who mixed Theosophical occultism with anti-Semitism and the doctrine of the racial supremacy of the Aryan or Indo-European peoples.”

Vril Powered Nazi UFOs?

Perhaps the most wild claims still circulating about the Vril Society, and its offshoot the Thule Society, is the legends of a secret Nazi UFO program.

Presumably the Vril Society established contact with the “Secret Chiefs” or the Vril-ya themselves, and secretly began cooperating with certain German scientists in the late 20’s.

As early as 1936 Hitler was sending teams of “Spelunkers” into caves and mines all over Europe searching for the Vril-ya.

The Nazi’s had also explored Antarctica extensively during the years 1937-38. In search of the fabled hole of the South Pole they apparently had success, like Admiral Byrd, in discovering these entrances.

It was here that some say they made contact with the “Unknown Superman” who lived in the fabled “Rainbow City“.

“In his controversial presentationUFO Secrets of the Third Reich,

Vladimir Terziskidraws a connection between alien beings and such German secret societies as the Tempelhoff, the Thule, the Vril, and the Black Sun.

Terziski tells of an “alien tutor race” that secretly began cooperating with certain German scientists in the late 1920’s in underground bases and began to introduce their concepts of philosophical, cultural, and technological progress.”

(

The Rainbow Conspiracy, p.62)

“With help from extraterrestrial intelligences, Terziski postulates, the Nazis mastered antigravity space flight, established space stations, accomplished

time travel, and

developed their spacecraftto warp speeds. At the same time the aliens “spread their Mephistophelean ideas” into the wider German population through the Thule and Vril Societies.”

click image to enlarge

“Terziski maintains that antigravity research began in Germany in the 1920’s with the first hybrid antigravity circular craft,

the RFZ-1, constructed by the Vril Society.

In 1942-43 a series of antigravity machines culminated in the giant 350-foot long, cigar-shaped Andromeda space station (above image), which was constructed in old zeppelin hangars near Berlin by E4, the research and development arm of the SS.”

(ibid p.62,

A familiar tune by now for those familiar with UFOlore.

Many books have claimed this as well – although none of them seem to agree on one particular scenario. Many photographs have also turned up as would be expected. Some have been exposed as hoaxes while others remain “unknowns”.

The Allies confiscated every scrap of Nazi documents, and most are still classified to this day. It is well known that the Germans had some out-of-this-world research for the time. Incidentally, the Vril Society’s existence was verified in the pilfered records and is in the possession of the British.

If in fact the Vril-Ya do exist and the Nazis did indeed establish contact with this superior race, then we could assume that this antigravity propulsion worked on the principles of Vril force. On the other hand, the Nazis, it has already been established, were driven by occult groups, like the Vril society, whose workings extended into the reaches of just such a force that would lead to the discovery Vril. So whether the tale of the Vril-Ya is for real or not is besides the point. Many have discovered this force independently of Lytton’s work.

It will continue to be suppressed. And for exactly the reasons that Lytton warned about in his book.

by Gary Lachman

New Dawn 165

(Nov-Dec 2017)

from NewDawnMagazine Website

| Gary Lachman was born in Bayonne, New Jersey, but has lived in London, England since 1996. A founding member of the rock group Blondie, he is now a full time writer with more than a dozen books to his name, on topics ranging from the evolution of consciousness and the western esoteric tradition, to literature and suicide, and the history of popular culture. Lachman writes frequently for many journals in the US and UK, and lectures on his work in the US, UK, and Europe. His work has been translated into several languages. His website is httpS://www.garylachman.co.uk. |

In 1960 a book appeared in France that triggered a kind of revolution.

Not a political one, although one of the book’s authors had political ideas that slanted distinctly toward the right. It was more a revolution of the mind, of the imagination we might say, or even of reality itself.

In the Paris of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, of existentialism, black polo necks, engagement and dreary “authenticity,” the book had the effect of a flying saucer landing at the Café Deux Magots, or of a cosmic wormhole opening in Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

In the black and white world of “nausea” and the “absurd,” Marxism and social commitment, it seemed to explode with technicolour visions of a strange new world.

Or perhaps a strange old one, a forgotten past that at the start of that most modern of decades, seemed poised to return to lead a new generation into a fantastic future.

The book was Le Matin des magiciens, or as it was soon called in its American edition, The Morning of the Magicians (The Dawn of Magic in the UK).

Its authors were an unlikely pair.

Louis Pauwelswas a journalist who had edited a hostile, misleading book about the enigmatic esoteric teacher

Pauwels had spent his last years in Paris and edited the newspaper Combat after the end of World War II; a previous editor had been Camus himself.

The Russian born Jacques Bergier was a physicist and chemical engineer with an interest in alchemy and a colorful past as a spy and resistance fighter.

The two met while working on a series of articles on contemporary science for a popular Parisian journal.

Accounts have it that they were introduced by André Breton, the Black Pope of Surrealism, who had a distinct interest in magic himself, as his exploration of the Tarot, Arcane 17, shows.

If true, then the revolution sparked by his introduction proved more influential and widespread than the one Breton had hoped Surrealism itself would bring about.

|  |

| Jacques Bergier (1912–1978) was a nuclear physicist and chemical engineer who was active in the French Resistance in World War II and helped destroy the German atomic plant at Peenemünde. | Louis Pauwels (1920–1997) was a French journalist who founded the magazine Planète, an outgrowth of Le Matin des magiciens. |

Pauwels and Bergier soon discovered they had much in common.

They shared a central insight, dissatisfaction with what they saw as the unnecessary limits of modern science, a constraint many find still in place today.

Pauwels had already spent several years investigating various schools of ‘alternative thought’.

Along with spending time in Gurdjieff’s groups in the late 1940s, he had also explored the teachings of Swami Vivekananda and the Traditionalism of René Guénon.

Bergier too came from a somewhat mystical background; he often spoke of a great-uncle in Russia who had been known as a ‘miraculous rabbi’.

Bergier had trained with the physicist André Helbronner, whose area of inquiry was the transmutation of elements, the essence of alchemy. Helbronner was murdered by the Nazis at Buchenwald and Bergier himself spent time in Mauthausen.

After his release, he became a spy for the Allies.

On one mission he discovered that the Germans had a secret supply of uranium, evidence, it seemed, the Nazis were close to making their own atomic bomb.

Bergier also claimed that in 1937 he met the elusive Fulcanelli, one of the most mysterious figures in the history of alchemy.

Fulcanelli was believed to have discovered the secret of the philosopher’s stone and in his work Le Mystère des Cathédrales he revealed the hidden meanings of the alchemical “green language,” the esoteric symbols carved in stone in the great Gothic masterpieces of Chartres and Notre Dame de Paris.

(Another said to have known Fulcanelli was the maverick Egyptologist René Schwaller de Lubicz, who claimed Fulcanelli stole the manuscript of Le Mystère des Cathédrales from him.)

In the 1950s, Bergier’s name was linked to the American weird fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft, who had acquired a critical cachet in France denied him in his homeland. His fascination with Lovecraft’s work was long-lived.

A letter Bergier wrote praising Lovecraft’s work was published in Weird Tales in 1936; another letter was published a year and a half later, lamenting Lovecraft’s death in 1937.

Pauwels and Bergier decided to write a book, exploring their ideas.

For five years they gathered material, haunting libraries and periodical rooms, rummaging through newspapers, magazines, and scientific journals, seeking out curious and little-known bookshops.

They studied ancient texts, investigated abandoned practices, and pored over reports of strange phenomena that were overlooked or actively ignored by the mainstream, creating their own kind of ‘X-Files’.

They aimed to show how practices like alchemy, long dismissed by the modern mind, had many parallels with modern physics, and that in some strange way the modern age fast coming upon us might have more to do with ancient insights found in magic and the occult than we would suspect.

In a way, they wanted to do for the post-war world what Madame Blavatsky had done a century earlier with her unwieldy masterpiece Isis Unveiled (1877): bring science up to date with the latest secrets from the remote past.

This was in line with their belief that,

“As a preliminary to understanding the present one must be capable of projecting one’s intelligence far into the past and far into the future.” 1

Their publisher, Éditions Gallimard, assumed the book would have modest success.

They were unprepared for the reception it received. France had a long history of interest in the occult – Gurdjieff himself had died only a decade earlier – but in 1960, angst was still the rage, and the bleak milieu of Waiting for Godot, with its grim comic nihilism, was still au courant.

That a book on magic and alternate realities would set the Seine on fire was hardly to be expected.

Yet, within weeks of publication, Le Matin des magiciens had both banks of the river talking about things that left existentialists scratching their heads.

While Allen Ginsberg howled in the Beat Hotel and American tourists slipped editions of the scandalous Olympia Press into their suitcases, amazed readers of Pauwels and Bergier were talking about,

alchemy, spacemen, lost civilizations, magic, occultism, quantum physics, secret societies, altered states of consciousness, the weird discoveries ofCharles Fort, forgotten groups like theHermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and its once notorious members, like the dark magician

Aleister Crowleyand much, much more.

Kick-Starting the “Occult Revival of the 1960s”

The book was a hit…

It seemed to appear at just the right time and took everyone by storm. In the process, it kick-started what became known as the “occult revival of the 1960s,” ushering in an occult boom that lasted into the 1970s and remains with us today as the New Age.

Les Matin des magiciens went on to sell millions of copies in France, and by 1963 there were UK and US editions, which did just as well.

The long post-war drabness and futility had lifted and a bright, exciting, and marvelous future, filled with mystery and miracle, seemed to beckon.

The book’s basic message, that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of by rive gauche philosophers, caught on. Paris-Presse called it,

“One of the most exciting books of our time.”

Le Monde devoted two long articles to its success, and that of Planète, the magazine that Pauwels and Bergier quickly started in magiciens wake.

No longer were we stuck in our ‘historical moment’, as existentialists had said.

The readers of Planète found that for 5.50 francs – not cheap at the time – they could investigate the ancient past, stretch their minds into the far-flung future, dive deep into their own inner worlds, or journey out into the stars.

Many Frenchmen did…

At its height, Planète had a bi-monthly circulation of more than 100,000, an impressive showing for a journal of its kind.

Although it did not translate into the English-speaking world as had Les Matin des magiciens, Planète was a success in Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, and conferences devoted to its themes were held in places as far-flung as Canada and Argentina.

Buenos Aires was home to the writer Jorge Luis Borges, who shared Pauwels and Bergier’s taste for what they called “fantastic realism”; his work appeared in several issues and he participated in the conference held there.

Along with Borges, Planète’s pages were home to other writers well-known to European readers, such as the ufologist Aimé Michel, the science fiction writer George Langelann – whose story ‘The Fly’ was the basis for several films – and the cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans, among many others.

Articles ranged from “A New Science of Dreams” and “Korzybski and General Semantics,” to “The True Woman of the Thousand and One Nights” and “A Mutant of the Eighteenth Century,” with reprints of works by C.S. Lewis, the Austrian occult novelist Gustav Meyrink, Salvador Dali, and others.

With its wide range of subjects and eclectic editorial brief – “Nothing that’s strange is foreign to us” was its motto – Planète catered to the burgeoning taste for the new, the marvelous, the unusual and magical that characterized the decade of the “mystic Sixties,” with articles on science, literature, archaeology, film, history, occultism, and much else.

Workshops and clubs based on Planète’s themes were opened in Egypt, India, and Mexico.

Its reach was global, we could even say planetary, and its impact was, like that of the book that spawned it, eventually felt around the world.

Reality is Much More Fantastic Than We Imagine

The 1950s had seen some other odd best-sellers.

Immanuel Velikovsky‘s Worlds in Collision, for example, published in 1950,hadrevived the catastrophe theory of cosmology by arguing that a comet sprung from Jupiter just missed Earth but destroyed Atlantis and caused several biblical miracles as it passed by.

It sold millions of copies.

In 1956 the Englishman Cyril Henry Hoskins started a long and successful career with his book The Third Eye: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Lama, written under the pseudonym T. Lobsang Rampa.

That Hoskins, a plumber, had never journeyed far from his home in Devon, England, seemed no obstacle to this account of his past life in the Himalayas, and his millions of readers agreed.

But The Morning of the Magicians – the edition I knew – was different than these and other popular books about flying saucers, like George Adamski‘s Flying Saucers Have Landed (1953) or suburban witchcraft, like Gerald Gardner‘s Witchcraft Today (1954).

It tried to link together, however loosely, a variety of unusual phenomena and ideas, in most cases with little more than their sheer strangeness.

It argued a point of view, the idea that reality is already much more fantastic than we imagine, and that if we peek beneath its surface, we will discover the strange connections linking everything together.

This may be the roots of a ‘conspiracy consciousness’, but it is also the beginning of a sense of a deeper meaning, hidden somewhere within the everyday world, that we can discover if we look for it.

Where Lovecraft, a familiar figure to Planète readers, warns us not to connect the dots, for fear of discovering a maddening reality:

“the most merciful thing in the world,” he tells us, “is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.”

Pauwels and Bergier positively insist that we do so.

For them, reality is not devastating, but fantastic, and their pursuit of it is not an escape from life – as it is for many romantics – but a deeper participation in it. The fantastic was reached by making contact with reality directly, by throwing off old habits of mind and prejudices of thought and opening consciousness to new possibilities.

It was reached through what Pauwels and Bergier, borrowing from Gurdjieff, called “the awakened state,” a new way of understanding reality, beyond the usual limits of “yes” or “no” that keep us hypnotized. 2

It was this aspect of the book that attracted the praise of important figures like the philosopher Edgar Morin and the writer Umberto Eco.

For the historian of religion Mircea Eliade, what was “new and exhilarating” about The Morning of the Magicians,

“was the optimistic and holistic outlook… in which human life again became meaningful and promised an endless perfectibility.”

We were called to,

“conquer the physical universe and to unravel the other, enigmatic universes revealed by occultists and gnostics.” 3

Not all shared Eliade’s appreciation.

Some, like the scholar of esotericism Antoine Faivre, who knew Pauwels and Bergier, saw the book as little more than a,

“masterpiece of confusionism” and “an adroit commercial undertaking.” 4

That it was a commercial success is undoubted, yet an honest appraisal must admit to some “confusionism” as well.

An attentive reader soon encounters it.

The book is full of inaccuracies, its breathless prose often trips over itself with sensational claims, its research is questionable, and references are at a premium…

It is, as Colin Wilson wrote, a “curious hodgepodge of a book,” “too wild and undisciplined,” and lacking a connecting thread linking together its ideas about a hollow earth, ancient astronauts, lost civilizations and dozens of other strange items. 5

In this, it suffers the same defect as the books of Charles Fort, a central influence on Pauwels and Bergier, and which also hampers their later collaborations Eternal Man (1972) and Impossible Possibilities (1974), neither of which have the same magic as their first effort.

Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled, mentioned earlier, has the same problem:

it presents an enormous amount of material which, while undoubtedly startling and exciting, soon begins to numb through sheer excess.

Probably the most serious inaccuracies in the book involve the alleged occult interests of Hitler and the Nazis, dubious claims about dark forces at work behind the Fuehrer that have gone on to spawn a whole genre of suspect literature, and which seeped into music, film and other areas of culture.

Serious investigations into the “occult roots of National Socialism” done by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Hans Thomas Hakl and others throw doubt on most of the claims made about “occult Nazism” in The Morning of the Magicians.

There are other ‘mistakes’ – those about the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn deserve special mention – but the general shakiness of many of Pauwels and Bergier’s claims has led the book to be categorized by later readers as a “grab-bag of inspiring misinformation.”

In this it is much like the work of an earlier Frenchman with a taste for the occult, Éliphas Lévi, whose gripping and highly readable books on Kabbalah and magic, while inspiring many young occultists – myself included – are nevertheless peppered with mistakes and outright howlers.

Yet in one sense the sensationalism and inaccuracies of The Morning of the Magicians hardly matter; in the occult genre, sadly, they are often the norm. Whatever the book’s flaws, its place in the counter-history of western consciousness is secure.

As I say in Turn Off Your Mind, my history of the influence of occult ideas on the 1960s, one of the remarkable things about The Morning of the Magicians is that it seemed to presage many of the themes that would come to dominate that decade. 6

For one thing, it heralded the ancient astronaut craze that hit the screen with Stanley Kubrick’s psychedelic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968) and made Erich von Däniken, author of Chariots of the Gods (1969),a rich man.

But perhaps even more significant was its anticipation of the youth rebellion that would characterise the times.

One of the central themes of The Morning of the Magicians is that of the mutant, young individuals with strange abilities, who are evolving into a higher type of human, and who stand out from the average.

Pauwels and Bergier give many examples of this phenomenon, but they were not alone.

Around the same time ‘The Village of the Damned’ (1960), the film version of John Wyndham‘s novel The Midwich Cuckoos, was released.

It tells the story of a strange meteor shower that leaves the young women of a small English village pregnant, although many are virgins. The children turn out to be part of a collective mind, possessing enormous intellects and strange mental powers.

And in 1963 Marvel Comics started what was to become one of its most successful series, The X-Men. This featured teenagers who, like the mutants of ‘The Village of the Damned’, possess weird powers and band together for support in a world that won’t accept them.

Not long after this, other, real-life teenagers felt something similar.

In Haight-Ashbury in 1967 the San Francisco Oracle, the psychedelic spreadsheet for the Aquarian Age, published a “Manifesto for Mutants.”

It proclaimed:

Mutants! Know now that you exist!

They have hid you in cities

And clothed you in fools clothes

Know now that you are free.

By then the occult revival, spawned by The Morning of the Magicians, was in full swing.

The fantastic realism that its authors sought to awaken in their readers seemed, at least for a time, to have taken to the streets.

If the ‘reality revolution’ of that mystic decade eventually petered out – Planète itself stopped publishing in 1972, Bergier died in 1978 and Pauwels in 1997 – the light of that magical morning nevertheless still shines today…

Footnotes

- Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, The Morning of the Magicians, Dorset Press, 1988, vii

- Ibid., 96

- Mircea Eliade, Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashion, University of Chicago Press, 1976, 10

- Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism, SUNY Press, 1996, 104

- Colin Wilson, The Supernatural, Carrol & Graf, 1991, 1-2

- Gary Lachman, Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius, Disinformation Books, 2003, 19; expanded UK edition The Dedalus Book of the 1960s; Turn Off Your Mind, Dedalus Books, 2009