CHAPTER 11

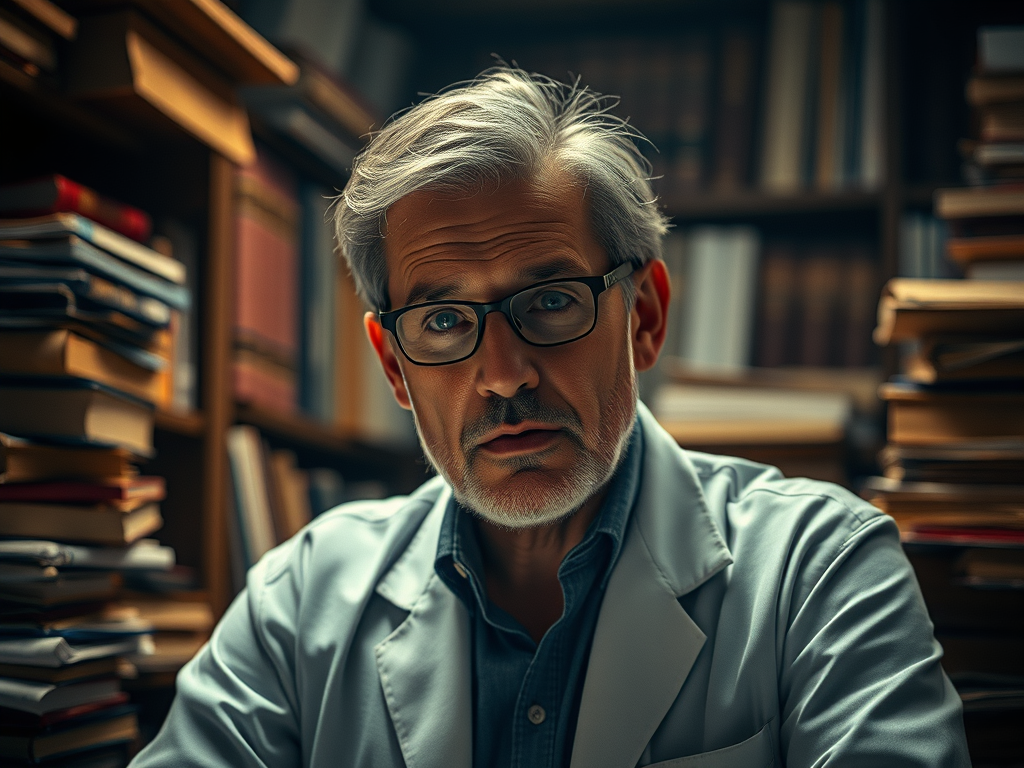

Michael Riconosciuto had some, if not all, of the answers to the gene splicing technology that Zokosky and Wackenhut had attempted to sell to the Army weapons division in 1983, and later fronted to the Japanese, through Meridian International Logisitcs, in 1988.

I felt that time was of the essence in uncovering the nature of this technology, so I pushed Riconosciuto to talk about it.

“It looks like Earl Brian, Sir Denis Kendall, Hercules Research, Wackenut, Zokosky and Bob Nichols were all involved in the same biotechnological agenda …”

Michael answered, “You got it.”

I asked, “Are they connected, or are they all individually working on their own projects?”

Michael: “Yes.”

“How?”

Michael: “Check out Bio-Rad Laboratories. Their international headquarters are on half of the property that used to be the Hercules plant, in Hercules, California. Do you understand what I’m saying? BioRad makes the most toxic biological and radioactive compounds known to man. And they’re now located in the town of Hercules. BioRad Industrial Park. That building of theirs, the headquarters, doesn’t look like much, but it goes 20 stories down into the ground. It’s a huge underground complex.

“See, BioRad was the flagship company, and then they [Earl Brian] started InfoTech, and then they got mired in lawsuits and then Hadron was formed to be a cutout parent corporation, you know, just to be a firewall from law suits …”

I asked, “What do they do at BioRad?”

“Well, they make the most hazardous biological and nuclear chemicals in the world, for medical research.”

“Who do they sell it to?”

“Well, front line researchers all over the world. BioRad is the single source for this stuff … actually Aldrich Chemical sells it, there’s about 100 companies, but BioRad is head and shoulder above all of them by a factor of ten on many things like Cytotoxins.”

I remembered reading about Cytotoxins in the Wackenhut/Cabazon biological warfare letters to Dr. Harry Fair.

Michael continued … “You look at Cytotoxic TLymphocytes. You go ask any medical professional what they’re doing on the leading edge of research there? What the full implications to humanity are, OK?”

I wanted clarification from Michael, so I answered, “It looks to me like research on a cure for cancer.”

Michael took the bait. “Go ask a professional. I’d rather have you hear it from a collateral source other than from me.”

“Well, give me some indication …”

Michael responded hesitantly, “It would have been Hitler’s wet dream. It’s selective to such a degree that it’s awesome. With the appropriate genetic material, you can wipe out whole segments of humanity. There’s no stopping it.”

“I asked, “You mean you could selectively wipe out certain races of people?”

“Sure.”

“Jeez.”

Mike continued …”And, also, from the beneficial side, you can very specifically wipe out disease cells, cancer cells. Look at the patents. Look at Immunix (phonetic sp.) Corporation, look at the patent portfolios on BioRad.”

“Who’s BioRad’s main buyer?”

“Well, the National Institute of Health, you know, every hospital in the world buys BioRad products.”

I had read about Sir Denis Kendall, the famous M16 British intelligence officer during World War II, in “Who’s Who in America,” 1989 issue. Kendall had worked with Michael in some, as yet, undefined capacity. Bobby Riconosciuto had noted to me that Kendall and Ted Gunderson had counseled Oliver North prior to his testimony to Congress. Kendall was also heavily involved in arms and biotechnology, according to Michael Riconosciuto.

“Who’s Who” described Denis William Kendall as a “medical electronic equipment company executive,” born in Halifax, Yorkshire, England on May 27, 1903. Kendall came to the United States in 1923, was naturalized in 1957. His background included being a consultant to the Pentagon on high velocity small arms from 1940 to 1945. He was listed on Churchill’s War Cabinet Gun Board from 194145. He was later executive vice president of Brunswick Ordnance Plant in New Jersey from 1952 to 1956. From 1961 to 1973, became president of Dynapower Medonics in Los Angeles, and chief executive of Kendall Medical International, Inc. in Los Angeles in 1973.

In 1983, the same year that Wackenhut was offering biological warfare agents to the Army, Sir Denis Kendall was the chairman of Steron Products, Inc. His club membership listings indicated he was a 32 degree Shriner in the Pacific Palisades (California) Masons and a member of the Religious Society of Friends (Quaker), amongst other things.

I asked Riconosciuto, “What was Sir Denis Kendall’s connection …?”

Michael broke in …”He’s involved in all of it. You might be able to get a handle on Kendall through Tiny Roland, a subsidiary of which is Penguin Books. And the other goodoleboy in the nail work is Octav Botnar. Then there’s Wolfgang Fosog (phonetic sp.), Renee Hanner, Count Otto Linkee (phonetic sp.) …”

“How did you meet these guys?”

“I was introduced through Joe Snell and Norman Davis. Snell was considered the father of industrial design. He was an industrial design artist who did the logos for Coca Cola, Channel No. 5, Life Magazine. Norm Davis owned (unintelligible) brewery until he sold to Carling. My dad was his advertising and public relations man. My dad didn’t know Kendall personally, but Norm Davis did. I met Kendall through Davis.”

“Do you know what Kendall is into currently?”

“Sure.”

“What would that be?”

“There’s a pharmaceutical company in Los Angeles. There’s a medical electronics company … Ted Shannon in Los Angeles supervises all the production for that stuff. It’s very exotic, far out stuff. And he’s still in a controlling position in Brunswick [Ordnance] Corporation.”

I asked Riconosciuto, “How close was BioRad to your father’s plant, Hercules?”

Mike answered, “It’s on the same property!”

“Mike, when you were conducting research at Hercules, you were incubating something in fish tanks there. What was it?”

Michael’s response had a nervous edge to it. “Where … where are you getting this?”

Riconosciuto was unaware at that point that his hidden files were in my possession. “I’m just thumbing through some old documents …”

” … Those documents aren’t supposed to exist any more. They’ve all been destroyed.”

“By whom?”

“Well, it was a matter of routine, you know … they COULDN’T exist …””

“Uh, huh.”

“That’s what they’re doing with all this stock manipulation, you know. The biologicals are what got them in the door at such a high level in Japan …”

I sensed Riconosciuto’s possible involvement in the project, his reluctance to discuss it. But he believed I had “all” the records and he stammered on. ” … That paperwork trail shouldn’t exist. I mean it was kept in a safe place, and then it was shredded. And the only people that had any direct knowledge of it was [Peter] Zokosky and Earl Barber, John Nichols, Bob Nichols, you know, those people …”

Michael was attempting to disengage himself from any responsibility for the research.

” … If there are any records left, those are their records, not any of ours [at Hercules], because I’m sure all of ours were destroyed.”

I asked, “Why did you destroy them?”

“Well, do you understand the nature of this technology? You’re talking in vague, general terms.”

I answered, “I have an idea …”

Michael interjected, ” … Horrible things. You know, it makes what the Nazi’s did to the Jews look mild. The Romanian Project, do your homework on that project, you know it’s a horrible germ warfare project …”

“Uh, huh.”

” … And the Soviets were involved in it, and we countered it with our own methods.”

I noted to Michael that Bill Turner, the man who had met Danny Casolaro in the parking lot of the Sheraton Martinsburg Inn (with Hughes Aircraft documents) on the day before his death, was currently in jail. Turner had written a letter in which he talked about an Iraqi from the Iraqi Embassy who was facilitating the transportation of biological warfare items to Iraq.

Michael responded, “Listen, Saddam Hussein introduced chemical and biological warfare agents to all his top military leaders. And he became enamored with this technology. He’s been on a binge of sorts. Even when he was in the secret police of Iraq, he used chemical means on a wide scale …”

I asked, “But none of these various entities that I’ve just named were dealing directly with Iraq, were they?”

“No, no. Not directly. All they needed was a VENDORS LIST.”

Riconosciuto noted that the shipments were all ITAR (International Trafficking of Armaments) regulated chemicals, electronics, communications equipment, anything that was on the ITAR list.

******

In August, 1991, the Financial Post ran a story on Dr. Earl Brian. At that time, Brian’s main company, Infotechnology Inc. of New York was bankrupt, and its subsidiary United Press International (UPI) was on the verge of collapse.

According to the Financial Post, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the FBI were investigating Brian, and a flurry of affidavits filed in the Inslaw Inc. scandal accused him of selling bootleg copies of the computer company’s casetracking software (PROMIS) to the intelligence services of Canada, Israel, and Iraq.

Brian was referred to as “Cash” in the intelligence community and reportedly had a close relationship with the CIA. He was a highly decorated combat surgeon in the Vietnam war in the late 1960’s, allegedly working in the controversial Phoenix Program. This, according to a 1993 “Wired,” premier issue, entitled “INSLAW, The Inslaw Octopus” by Richard L. Fricker. Wrote Fricker, “After a stint in Vietnam, where he [Brian] worked as a combat physician in the unit that supplied air support for Operation Phoenix, Brian returned to California …”

In 1970, Ronald Reagan appointed Brian director of the California Department of Health Care Services. He was only 27 and destined to remain a part of Reagan’s inner sanctum. U.S. and Israeli intelligence sources linked Brian’s name to the sale of weapons to Iran in the 1980’s. “He was serving U.S. intelligence people, ” said Ari BenMenashe, a former Israeli intelligence officer who claims he met Brian several times, once in Tel Aviv. Brian allegedly had more to do with the financial end of the transactions.

Other publications listed Brian’s holdings in the rapidly developing biotechnology field. The hightech empire of Dr. Brian was a grab bag of fledgling companies involved in all the hot areas lasers, cancer detection kits, blood-testing products, genetic engineering, computer programs, telecommunications and investment databases.

One of Brian’s companies, Hadron, Inc. of Fairfax, Virginia, which, incidentally, both Michael Riconosciuto and Robert Nichols maintained Peter Viedenieks was involved in, was a laser manufacturer and computer services company.

According to Bill Hamilton, president of Inslaw, Hadron had attempted to buy Inslaw in 1983. Dominic Laiti, Hadron’s chairman at the time, had phoned Hamilton out of the blue and said Hadron intended to become a dominant vendor of software to law enforcement agencies. Would Hamilton like to sell? Hamilton demurred. “We have ways of making you sell,” Laiti is said to have replied.

Laiti, in an interview in 1988 with the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, said he didn’t remember calling Hamilton. Nevertheless, Hamilton said he believes his rejection of Hadron on that day in 1983 triggered an attempt by the Department of Justice to put Inslaw out of business, or at least bankrupt the small, Washington-based software maker.

At that time, Peter Viedenieks was the administrator of the contract between Inslaw and the DOJ. Within a few months of Hadron’s call, the Department of Justice, citing contract violations, stopped making payments on Inslaw’s $10 million deal to install PROMIS software in its 20 largest U.S. attorney’s offices nationwide. (PROMIS stands for Prosecutor’s Management Information System.)

Inslaw, starved of cash, was forced into Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 1985. Hamilton sued the DOJ for theft of property in 1986.

In February 1988, Federal Bankruptcy Court Judge George Bason ordered the DOJ to pay Inslaw $7 million in licensing and legal fees. The DOJ, Bason ruled, had “stolen PROMIS from Inslaw through trickery, fraud and deceit,” then tried to put the company out of business.

The DOJ appealed Bason’s ruling, but it was upheld. However in May, the U.S Court of Appeals reversed the decision on a technicality. Hamilton believed Dr. Brian and his old crony, former Attorney General Edwin Meese, were behind the attempt to bankrupt and liquidate Inslaw. When Inslaw refused to sell to Hadron, Hamilton believed the DOJ tried to bankrupt and liquidate Inslaw to force the sale of its assets, perhaps to Hadron, at firesale prices.

Several journalistic publications accused Dr. Brian of profiting from the Justice Department’s theft of the PROMIS software. According to a number of sources, Brian traveled the world during the mideighties, selling the data management program to intelligence and law enforcement agencies the world over.

Brian’s role, if any, in the October Surprise was less well publicized. The primary source thus far for the allegations that Brian was involved, is former Israeli intelligence officer Ari BenMenashe. Menashe alleged that Earl Brian helped make one of the first contacts between Republicans and the government of Iran in 1980. BenMenashe claimed Brian accompanied Robert C. “Bud” McFarlane to Tehran in late February 1980. The trip came shortly after the New Hampshire primary, when insiders knew that there would be a ReaganBush ticket.

Earl Brian and McFarlane, then an aide to Senator John Tower (RTX), allegedly contacted Iranians with whom Brian had conducted business prior to the fall of the Shah. According to BenMenashe, one of these was Mehdi Bazargan, onetime Prime Minister, and in February 1980 still closely connected to the Iranian leadership.

An old 1975 Sacramento Bee newspaper article, dated January 12, 1975, reported that Earl Brian, called the Genius Doctor by his friends, was out to get a little “of that Middle Eastern oil money.” The article went on to say that Brian was “helping to write a proposal on health care for Iran.”

Brian, then at the University of Southern California, was working with Samuel Tibbetts of the California Lutheran Hospital Association, which in turn was working with a Chicago group. The Chicago group was not named and details of the proposal were not known. It is significant that Brian left his post one year before this proposal was written, in 1974, as Governor Ronald Reagan’s Health and Welfare secretary. It was not known whether the contract with the Iranian government was ever consummated.

Another interesting facet of Brian’s background included his relationship with Senator Terry Sanford (DN.C.). Prior to his election, Sanford had been the attorney representing Earl Brian in his 1985 takeover bid for United Press International (UPI). Sanford was also instrumental in winning Brian an appointment to the board of Duke University Medical School. At that time, Sanford was the president of Duke University.

Dr. Brian ultimately directed his energies towards biological technology. Another of his companies, Biotech Capital Corporation of New York, became 50% owner of American Cytogenetics, which was planning in 1982 to create a subsidiary to engage in genetic research. One notable investor in Biotech, when it went public in 1981, was Edwin Meese. Today, American Cytogenetics in North Hollywood, California, conducts Pap tests for cervical cancer. It also tests tissue samples for cancer and related diseases. Sales in 1985 were $3.4 million.

Hadron, of which Dr. Brian was a director, provided engineering and computer consulting services, along with telecommunications products. Sales were $25.7 million in 1985. Clinical Sciences, Inc. sells biochemical products used for diagnostic tests and antibody analysis. Dr. Brian was also a director of this company. Sales in 1986 were about $4 million.

******

Michael Riconosciuto had stated that he believed Earl Brian held a financial interest in Bio-Rad Laboratories in Hercules, California. I was unable to locate Brian’s name in Board directories, but obtained some documents on an OEM agreement between California Integrated Diagnostics, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of the InFerGene Company, (“Manufacturer”) a Delaware corporation, and BioRad Laboratories, Inc. (“Customer”) a Delaware corporation, which listed the terms under which the manufacturer would provide the customer with various products.

Various exhibits outlined the product price list, delivery schedules, engineering specifications, etc. What made this agreement significant was a newspaper article published in the San Francisco Chronicle on May 31, 1991, entitled, “S.F. Firm Faces Toxics Charges.” A criminal complaint had been filed against a law firm, an investment banking house and several lawyers and financiers involved with InFerGene Company for abandoning its toxic wastes after filing for bankruptcy.

According to an affidavit filed by the Solano County District Attorney’s office at the Fairfield Municipal Court, after InFerGene was evicted from the premises, a county inspector found several hundred containers including petri dishes and vials marked “chlamydia, herpes, and HSV2.” Many others contained “bacteria of unknown etiology.”

A Vacaville newspaper reported that on December 7, an environmental health inspector found 36 55gallon drums of radioactive Butanol containing “beef mucosa.” They were improperly stored and lacked labels showing content, hazard warning or the owner’s business address. A followup report made by the environmental health office noted that a Halloween 1990 investigation into a smell was traced to a door with a radiation warning on it. The department had recommended that the lab doors be sealed and the pipe opening sealed.

In all, the county Environmental Health Department had responded four times to complaints about smells from the InFerGene labs in the Benicia Industrial Park well before it shut down in February. One complaint listed persistent smells causing nausea, a problem also cited by others still working in the area.

Founded in 1983, InFerGene specialized in DNA technology, making diagnostic test kits for AIDS, hepatitis and other diseases.

My research led me to another article on Bay Area bio-labs. In June, 1991, the San Francisco Examiner published a story entitled, “Germ War Lab Alarms Berkeley” which noted the community of West Berkeley “was home to the Defense Department’s one and only supplier of anti-plague vaccine.” On December 28, 1990, four maintenance men made an unauthorized entrance into a room at Cutter Biological which housed Yersinia pestis, commonly known as “The Black Plague,” which once killed a quarter of the population of Europe 650 years ago.

There was no harm to the workers and no release of the live bacteria, but if an accident had occurred, all of Berkeley would have been wiped out.

******

It is impossible NOT to compare the two incidents in the San Francisco bay area with the Wackenhut proposal to develop biological warfare viruses on the Cabazon Indian reservation in Indio, California. In order to develop vaccines, which sounds innocuous enough, the virus must first be created. In the case of biological warfare viruses, the disease would have to be highly sophisticated indeed, if it were to be used in military applications. Certainly nothing that would be easily recognizable, if it escaped the laboratory, to a layman medical doctor in Indio, California, or for that matter at any Indian reservation in the United States.

Any type of biological research on an Indian reservation would not be subject to scrutiny by the federal government because Indian reservations are sovereign nations. Nevertheless, if a virus DID escape a secret government installation at an Indian reservation, the reservation would provide an ideally “isolated environment” for further study (by a government entity) of affected subjects or victims under quarantine. Not a very pretty picture. Yet this was the exact nature of the proposal by Wackenhut to Dr. Harry Fair of the Army weapons division.

For the first time, I began to notice various “mysterious” illnesses cropping up in the media. I’m sure there have been unidentified diseases throughout history, but for the first time, I was conscious of what was written about them.

The first to capture my attention was the sudden deaths of twelve Navajo Indians in New Mexico and Arizona. A June 3, 1993, Department of Health Services interoffice memorandum distributed to public health laboratory directors throughout California labeled the virus a “Mystery Illness in New Mexico and Arizona.” The memo asked, “Is it in California too?”

On June 2, 1993, New Mexico officials had reported a total of 19 cases, summarized as follows: Of the 19 cases, 12 were Native American Indians. Twelve died. All of the victims were residents within a 100 mile area in northwest New Mexico and Northeast Arizona. The symptoms included fulminant respiratory distress which killed within hours. There was “NO IDENTIFIABLE CAUSE.” This was printed in capital letters.

Under “Etiology” (origin), the memorandum noted, “[The illness] remains a mystery despite extensive testing at University of New Mexico Hospital, New Mexico Department of Health, and CDC. If etiology were plague, anthrax, tularemia, some cases should have been identified by cultures/stains …”

Oddly, nationwide media printed stories stating that the illnesses were caused by rat droppings, yet the actual documents from the Department of Health Services in Berkeley, California, confidentially given to me by a laboratory director in June 1993, mentioned nothing about rat droppings.

I later read about a mystery illness in TIME magazine, November 22, 1993 issue entitled, “The Gulf Gas Mystery,” which reported that American troops in the Persian Gulf, upon returning home, were complaining of chronic diarrhea, aches in all the joints, and difficulty breathing. Several veterans and their families testified before a congressional committee that the Defense Department had ignored their complaints, and the Veterans Affairs Department downplayed the affair. The veterans themselves were convinced they had been exposed to “disease-causing chemical agents” while in the Persian Gulf. Eight-thousand veterans registered their symptoms with the U.S. government, thus labeling the disease “Gulf War Syndrome” (GWS).

Ultimately, the disease was determined by Major General Ronald Blanck, commander of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, to be “multiple chemical sensitivity,” syndrome. A board of inquiry was created headed by Joshua Lederberg of Rockefeller University, a Nobel-prizewinning expert on rare and emerging diseases. But, noted TIME, “It is up to the Pentagon to bridge the credibility gap that seems to have sprouted over the strange new syndrome.” It was not until 1996 that the Pentagon admitted GWS may have been caused by exposure to bombed chemical/biological plants in Iraq.

By far the most provocative incident occurred in February, 1994. The SpokesmanReview, out of Spokane, Washington, printed a story on August 9, 1994, entitled, “Victim of Mysterious Fumes Seeks Investigative Reports.” In Riverside, California, the county in which the Cabazon Indian/Wackenhut facility is located, Dr. Julie Gorchynski, an emergency room doctor, was overcome by mysterious fumes while examining a woman who later died.

“This is a bona fide, genuine medical mystery, and we intend to solve it,” said Russell S. Kussman, attorney for Dr. Gorchynski. Gorchynski suffered from osteonecrosis, avascular necrosis of bone, posttraumatic stress disorder, shortness of breath, restrictive lung disease and other ailments, as a result of exposure to the dying cancer patient on February 19th. Coincidentally, her symptoms matched those of GWS.

Later, in the same newspaper, dated September 3, 1994, another article emerged regarding the Riverside mishap. The bizarre episode had sent six emergency room workers to hospitals after being exposed to fumes emitting from patient Gloria Ramirez’s blood samples drawn on February 19, 1994.

According to the state’s 15page report, 11 people reported smelling an unusual odor after blood was drawn from Ramirez. After five collapsed and the emergency room was evacuated, 23 people complained of at least one symptom, most commonly headache, dizziness, and nausea. More serious complaints included muscle spasms and breathing disruptions. “Despite extensive epidemiologic, toxicologic and environmental investigations, the cause of the outbreak of symptoms among emergency room staff members … remains unknown,” the report concluded.

Dr. Gorchynski’s lawyer stated that it could only be a toxin. “It’s physically impossible for Julie to have had the symptoms, and not just the symptoms, the laboratory findings and test results that showed … clearly Dr. Gorchynski was poisoned that day.”

But epidemiology experts could find no culprit to explain the bizarre episode. The Department of Health Services ultimately described the incident as an outbreak of “mass sociogenic illness,” perhaps triggered by an odor.

I could not help wondering if the deceased Gloria Ramirez was an Indian, or had ever been on the Cabazon reservation in Indio? I later learned she had been receiving experimental cancer treatments at a clinic in Mexico.

J.M., Ted Gunderson’s live-in partner, on more than one occasion had noted that she held in her possession a photograph of Gunderson and Sir Denis Kendall, the British M-I6 officer who owned bio-labs in Los Angeles, standing in front of a Mexican cancer clinic. According to J.M., the photo had been used in an advertisement seeking nurses to work at the clinic. Without a copy of the photo, I was unable to determine if it “might” be the same clinic which Gloria Ramirez attended prior to her death.

******

In February 1993, I was contacted by a U.S Customs agent who was conducting an inquiry into the whole Inslaw, Peter Viedenieks, Wackenhut affair. The man had flown in to California from back east to interview Mike and Bobby Riconosciuto and other witnesses associated with the Inslaw case. Someone, whom he would not identify, advised him to contact me.

On February 5th, he and his partner drove to my home in Mariposa and spent the day. I provided him with an affidavit relative to Riconosciuto’s attempted trade into the Witness Protection Program. The affidavit contained mostly drug-related information on The Company and Robert Booth Nichols’ connection to Michael Abbell (DOJ) and the Cali Cartel. The agent also obtained a tape-recorded statement, under oath, relative to my findings and left with an armload of documents. (Two years later, in 1995, Abbell was indicted for money laundering for the Cali Cartel and drug related charges).

He called frequently after that (1993), once from a phone booth in the dead of night after visiting Langley, Virginia. We subsequently struck up an investigative collaboration of sorts. On September 3, 1993, I received a call from him in Palm City, Florida. He had interviewed Robert Chasen, former Executive Vice President, Systems and Services Group, of Wackenhut Corporation in Coral Gables. Chasen, 70, was still senior consultant at the Florida facility, but was allegedly dying of cancer and weighed less than 100 pounds at the time of the interview.

Because he (Chasen) had once been Commissioner of Customs in Washington D.C., he felt a rapport with this young agent and spoke candidly about his experience with Wackenhut in Indio.

Of significance, was Chasen’s confirmation of the horrendous properties of the “virus” which he encountered at the Indio facility. He said, “Wackenhut was running amuck.” Robert Nichols and Peter Zokosky had attempted to sell the biological warfare technology (developed in cow uterises) through Wackenhut, using Robert Frye, Vice President of the Indio facility, as the front man.

According to Chasen, Frye went behind his [Chasen’s] back in facilitating the project; when Chasen learned of the project, he shut it down. (Chasen supervised the Indio facility from Coral Gables, Florida.) Because of the projects underway at the Cabazon reservation, Chasen chose not to step foot on the property, but instead met with the Indio executives in Palm Springs.

In other respects, Chasen was not so candid. Though the Customs agent said Chasen “said a lot of derogatory things about Wackenhut in Indio,” he did not admit to knowing Peter Viedenieks. The agent’s investigation had led him to believe that the PROMIS software WAS stolen, and Viedenieks WAS involved in the theft, but he did not have enough evidence to take his case to court.

Chasen was evasive on the subject of PROMIS, though his background would indicate that he must have been knowledgeable about it. He had been a Special Agent in the Washington D.C. Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1943 to 1952. From 1952 to 1968, he was Vice President and President, respectively, of ITT Communications Systems in Chicago, Illinois and Paramus, New Jersey. He became Commissioner of U.S. Customs in Washington D.C. from 1969 to 1977 the same time span that Peter Viedenieks was in and out of Customs.

I called Dick Russell (author of “The Man Who Knew Too Much“) to act as a “cutout” for me and interview Chasen. At that point, I didn’t want to expose myself to Wackenhut, so Russell agreed. When Russell called back, he said Chasen didn’t trust Robert Booth Nichols. Wackenhut had “run a check” on Nichols and couldn’t learn anything about his background. This had bothered Chasen, but, he said, Robert Frye and Dick Wilson were “dazzled” with Nichols.

Chasen believed Nichols worked for the CIA, said he was a “slippery guy,” and couldn’t understand why Frye and Wilson were dazzled by Nichols for such a long time. Reportedly, George Wackenhut liked Frye and Dick Wilson, but did not trust Riconosciuto or Nichols. Michael Riconosciuto had been introduced to Chasen as a “specialist engineer in weapons.”

Chasen acknowledged the biological technology introduced by Nichols and Zokosky, saying it had been presented to him as something that could “create anything from chicken soup to long range missiles.” When he learned of the properties of the technology, he halted it immediately. When pressed for further details, he added reluctantly, “It was the kind of thing your mind erases.”

Regarding the Cabazons, Chasen said he felt an affinity with Arthur Welmas, Chairman of the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, because his [Chasen’s] wife is part Cherokee. He noted that he sympathized with their situation and wanted to protect them.

Perhaps he protected them more than he realized when he shut down the Wackenhut proposal to the Army to develop biological viruses (and vaccines) on the Cabazon reservation.

******

One year later, on September 5, 1994, TIME magazine published an article on page 63 entitled, “A Deadly Virus Escapes,” in which a Yale University researcher was exposed to the deadly Brazilian “Sabia” virus when a container spinning on a high-speed centrifuge cracked, causing the potentially lethal tissue to spatter. Fortunately, the researcher was wearing a lab gown, latex gloves and a mask, as required by federal guidelines.

Every surface of the area was scrubbed with bleach, all instruments were sterilized, then wiped down again with alcohol. Having decided the danger was over, he didn’t bother to report the accident, and a few days later he left town to visit an old friend in Boston. Soon after the researcher returned to Yale, he began running a fever that reached 103 F.

An experimental antiviral drug eventually stopped the illness, but the man had exposed five people, including two children, before being confined to a hospital isolation ward, and another 75 or so healthcare workers after that.

The Sabia virus is particularly frightening because it kills in such a grisly way. Characteristic symptoms are high fever, uncontrolled bleeding in virtually every organ and finally shock. The liver turns yellow and decomposes. Blood can leak from literally every bodily orifice, including the eyes and the pores of the skin. Sabia was never seen before 1990, when a female agricultural engineer checked into a hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil, with a high fever. Within days she was dead.

Fortunately, in the Yale University incident, none of the potential victims died or showed any evidence of symptoms. A book and movie on the Sabia virus’s counterpart, the lethal Ebola virus from Central Africa, which is as deadly and as gruesome as AIDS, yet has an incubation period of only one week, was underway at the time and was later released in 1994.

The book, “The Hot Zone,” described a victim who contracted Ebola. TIME wrote,

“His eyes turn red and his head begins to ache. Red spots appear on his skin and, spreading quickly, become a rash of tiny blisters, and then the flesh rips. Blood begins to flow from every one of the body’s orifices. The victim coughs up black vomit, sloughing off parts of his tongue, throat and windpipe. His organs fill with blood and fail. He suffers seizures, splattering virus-saturated blood that can infect anyone nearby. Within a few days the victim dies, and as the virus destroys his remaining cells, much of his tissue actually liquefies …”

The Ebola virus, found in the rainforest regions of Central Africa, once caused an outbreak in 1976 through villages near the Ebola River in Zaire, killing as many as 90% of those infected. Such dangerous viruses may seem a distant menace, wrote TIME, but “The Hot Zone” details a 1989 Ebola crisis that occurred in the Reston, Virginia Primate Quarantine Unit, run by a company that imports and sells monkeys for use in research laboratories.

When an unusual number of monkeys originating from the Philippines died, tissue samples were sent to a U.S. Army research center. There a technician identified the strands as either Ebola Zaire or something very close. Even more alarming, the virus found in Reston, Virginia, unlike the African one, could be transmitted through the air. Frantic phone calls were made to Virginia health authorities and to the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta. An Army team, wearing space suits, went into the Reston building and killed 450 surviving monkeys, then placed them in plastic bags for safe disposal. Before the building was boarded up, the Army sterilized every square inch of the interior. No humans were infected with the virus, but Richard Preston, the author of “The Hot Zone,” wrote, “A tiny change in its genetic code, and it might [have] zoomed through the human race.”

A rival 1995 film on the same subject entitled, “Outbreak,” directed by Wolfgang Peterson, also focused on the Ebola virus.