from Wikipedia Website

A multiverse (or meta-universe) is the hypothetical set of multiple possible universes (including our universe) that together comprise all of reality. The different universes within a multiverse are sometimes called parallel universes.

The structure of the multiverse, the nature of each universe within it and the relationship between the various constituent universes, depend on the specific multiverse hypothesis considered.

Multiverses have been hypothesized in cosmology, physics, astronomy, philosophy, theology, and fiction, particularly in science fiction and fantasy. The specific term “multiverse,” which was coined by William James,[1] was popularized by science fiction author Michael Moorcock.

In these contexts, parallel universes are also called,

- “alternative universes”

- “quantum universes”

- “parallel worlds”

- “alternate realities”

- “alternative timelines,” etc.

The possibility of many universes raises various scientific and philosophical questions.

Multiverse hypotheses in physics

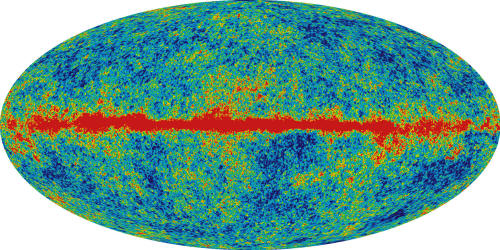

Laura Mersini-Houghton claims that the WMAP cold spot may provide testable empirical evidence for a parallel universe within the multiverse.

According to Max Tegmark,[2] the existence of other universes is a direct implication of cosmological observations.

Tegmark describes the set of related concepts which share the notion that there are universes beyond the familiar observable one, and goes on to provide a taxonomy of parallel universes organized by levels.[3]

Classification

In order to clarify terminology, George Ellis, U. Kirchner and W.R. Stoeger recommend using the term,

- “the Universe” for the theoretical model of the whole of the causally connected spacetime in which we live,

- “universe domain” for the observable universe or a similar part of the same space-time

- “universe” for a general space-time, either our own “Universe” or another one disconnected from our own

- “multiverse” for a set of disconnected space-times

- “multi-domain universe” to refer to a model of the whole of a single connected space-time in the sense of chaotic inflation models [4]

The levels according to Tegmark’s classification and using Ellis, Koechner and Stoeger’s terminology are briefly described below.

- Multi-domain universes (Ellis, Koechner and Stoeger sense) – Level I (Open multiverse) A generic prediction of cosmic inflation is an infinite ergodic universe, which, being infinite, must contain Hubble volumes realizing all initial conditions.

- Universes with different physical constants – Level II (Andrei Linde’s bubble theory) In chaotic inflation, other thermalized regions may have different effective physical constants, dimensionality and particle content. (Surprisingly, this level includes Wheeler’s oscillating universe theory as well.)

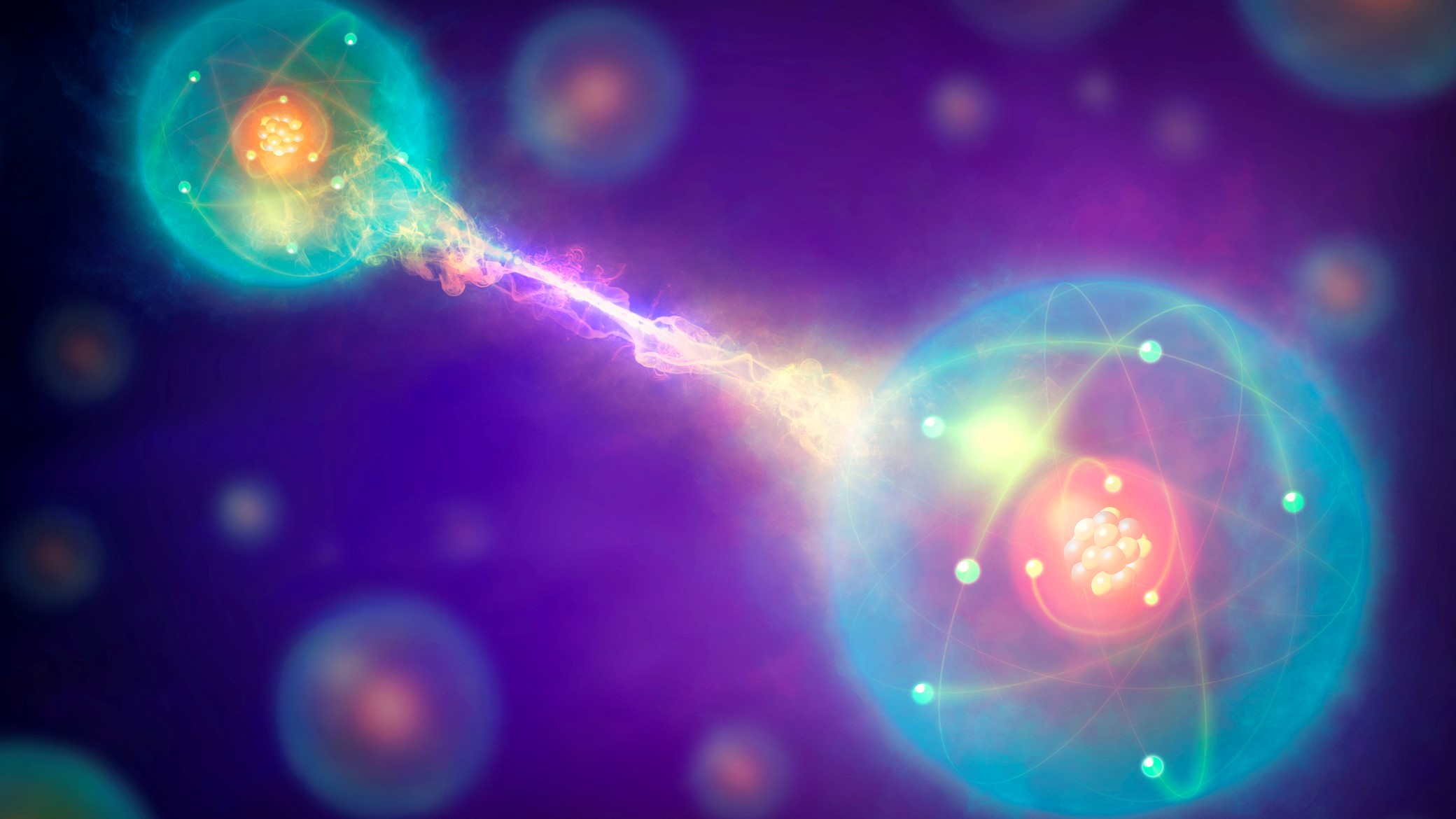

- Multiverses (Ellis, Koechner and Stoeger sense) – Level III (Hugh Everett III’s many-worlds interpretation) An interpretation of quantum mechanics that proposes the existence of multiple universes, all of which are “identical”, but exist in possibly different states. It is widely believed that Everett’s interpretation (considered as a formal theory) is a conservative extension of standard quantum mechanics – that is, as far as results expressible in the language of ordinary quantum mechanics are concerned, it leads to no new results. This, according to Tegmark, “is ironic given that this level has historically been the most controversial”. In September 2007 David Deutsch presented what is considered a proof of the many-worlds interpretation.[5] [6]

- Ultimate ensemble – Level IV (The ultimate “Ensemble theory” of Tegmark) Other mathematical structures give different fundamental equations of physics. This level considers “real” any hypothetical universe based on one of these structures. Since this subsumes all other possible ensembles, it brings closure to the hierarchy of multiverses: there cannot be a Level V. The question is open whether or not scientists will subdivide Level IV in the future.

Bubble theory

“Bubble universes”, every disk is a bubble universe (Universe 1 to Universe 6 are different bubbles, they have physical constants that are different from our universe), our universe is just one of the bubbles.

Bubble theory posits an infinite number of open multiverses, each with different physical constants. (The set of bubble universes is thus a Level II multiverse.)

Counter-intuitively, these universes are farther away than even the farthest universe in our open multiverse.

The formation of our universe from a “bubble” of a multiverse was proposed by Andre Linde. This Bubble universe theory fits well with the widely accepted theory of cosmic inflation. The bubble universe concept involves creation of universes from the quantum foam of a “parent universe.”

On very small scales, the foam is frothing due to energy fluctuations. These fluctuations may create tiny bubbles and wormholes. If the energy fluctuation is not very large, a tiny bubble universe may form, experience some expansion like an inflating balloon, and then contract and disappear from existence.

However, if the energy fluctuation is greater than a particular critical value, a tiny bubble universe forms from the parent universe, experiences long-term expansion, and allows matter and large-scale galactic structures to form.

Many worlds interpretation of quantum physics

Hugh Everett‘s many-worlds interpretation (MWI) is one of several mainstream interpretations of quantum mechanics.

Other interpretations include the Copenhagen and the consistent histories interpretations. The multiverse proposed by MWI has a shared time parameter. In most formulations, all the constituent universes are structurally identical to each other and though they have the same physical laws and values for the fundamental constants, they may exist in different states.

The constituent universes are furthermore non-communicating, in the sense that no information can pass between them, although in Everett’s formulation they may potentially affect each other[7] through quantum interference.[8]

The state of the entire multiverse is related to the states of the constituent universes by quantum superposition, and is described by a single universal wave-function.

Related are Richard Feynman‘s multiple histories interpretation and H. Dieter Zeh‘s many-minds interpretation.

Many worlds interpretation cannot explain the apparently Fine-tuned universe. The physical constants of all the “many worlds” are the same. Many worlds interpretation can, however explain the apparent improbability of a planet like Earth existing.

If the Many worlds interpretation is true there are so many copies of our universe that the existence of at least one planet like Earth is not surprising.

M-theory

A multiverse of a somewhat different kind has been envisaged within the 11-dimensional extension of string theory known as M-theory. In M-theory our universe and others are created by collisions between membranes in an 11-dimensional space.

Unlike the universes in the “quantum multiverse”, these universes can have different laws of physics.

String landscape

The string landscape theory asserts that a different universe exists for each of the very large ensemble of solutions generated when ten dimensional string theory is reduced to the four-dimensional low-energy world we see.

Criticisms of multiverse theories

Non-scientific claims

Critics claim that these theories lack empirical correlation and testability, and without hard physical evidence are unfalsifiable; outside the methodology of scientific investigation to confirm or disprove.

Bad science

Some have argued that the job of a scientist is to provide fundamental explanations for observed phenomena, without making reference to observers. Resorting to anthropic principles constitutes a “lazy way out” of accounting for features such as the apparent fine-tuning of parameters in relation to the existence of life.

Leonard Susskind claims, however, that some form of multiverse is unavoidable, given the current state of physics, and that observer effects are inevitable and have to be taken into account in other sciences.

Occam’s Razor

To postulate an infinity of unseen and unseeable universes just to explain the one we do see seems superficially contrary to Occam’s Razor.

Tegmark answers:

“A common feature of all four multiverse levels is that the simplest and arguably most elegant theory involves parallel universes by default.

To deny the existence of those universes, one needs to complicate the theory by adding experimentally unsupported processes and ad hoc postulates: finite space, wave function collapse and ontological asymmetry.

Our judgment therefore comes down to which we find more wasteful and inelegant: many worlds or many words.”[9]

Thus, according to Tegmark, paradoxically the multiverse scenario is more parsimonious than that of a single universe.

David Lewis, however, draws a distinction between qualitative and quantitative excess. Postulating extra universes just like our own does not increase the number of kinds of things there are, and thus there is only qualitative invariance.

One unique universe

It is sometimes argued that the observed universe is the unique possible universe, so that talk of “other” universes is ipso facto meaningless. Einstein raised this possibility when he wondered whether the universe could have been otherwise, or non-existent altogether.

This possibility is also expressed in theories such as determinism and chaos theory.

The hope is sometimes expressed that once a grand unified theory of everything is achieved, it will turn out to have a unique “solution” corresponding to the observed universe.

Other objections

The entire range of multiverse hypotheses, with specific emphasis on Hugh Everett’s many-worlds interpretation, have been criticized by proponents of intelligent design.

William Dembski in particular, derides it as inflating explanatory resources without evidence or warrant, and terms such concepts “inflatons”.[10]

Anthropic principle

The concept of other universes has been proposed to explain why our universe seems to be fine-tuned for conscious life as we experience it.

If there were a large number (possibly infinite) of different physical laws (or fundamental constants) in as many universes, some of these would have laws that were suitable for stars, planets and life to exist.

The anthropic principle could then be applied to conclude that we would only consciously exist in those universes which were finely-tuned for our conscious existence. Thus, while the probability might be extremely small that there is life in most of the multiverses, this scarcity of life-supporting universes does not imply intelligent design as the only explanation of our existence.

Critics of this argument (Steven Jay Gould, Richard Dawkins and many others) point out that the cause and the effect have been reversed by those who claim that the universe seems to be fine-tuned for our benefit.

Dr. Gould compared it to claiming that sausages were originally made long and narrow so that they would fit modern hotdog buns, or that humans evolved fingernails so that fingernail polish would be invented.

Critics cite the vast store of evolutionary evidence which shows that life is perfectly and naturally tuned to the universe it arose in. Fossil, genetic and other biological evidence abundantly supports the observation that life adapts to physics, not the other way around.

The paleophysicist Caroline Miller writes:

“The Anthropic Principle is based on the underlying belief that the universe was created for our benefit. Unfortunately for its adherents, all of the reality-based evidence at our disposal contradicts this belief.

In a non-anthropocentric universe, there is no need for multiple universes or supernatural entities to explain life as we know it.”

Modal realism

Additionally, possible worlds are a way of explaining probability, hypothetical statements and the like, and some philosophers such as David Lewis believe that all possible worlds exist, and are just as real as the actual world (a position known as modal realism).[11]

Trans-world identity

A metaphysical issue that crops up in multiverse schema that posit infinite identical copies of any given universe is that of the notion that there can be identical objects in different possible worlds.

According to the counterpart theory of David Lewis, the objects should be regarded as similar rather than identical.[12][13]

Virtual realities as a multiverse

Some scientists entertain the possibility of creating artificial conscious machines, and some artificial intelligence advocates even claim we are not far from producing conscious computers. It is then but a small step to the point where the engineered conscious beings inhabit a simulated reality.

For such beings, their “fake” universe will appear indistinguishable from reality.

Multiverse hypotheses in religions around the globe

Hindu universes

The earliest known records describing the concept of a multiverse are found in ancient Hindu cosmology, in texts such as the Puranas.

They expressed the idea of an infinite number of universes, each with its own gods, inhabitants and planets, and an infinite cycle of births, deaths, and rebirths of a universe, with each cycle lasting 8.4 billion years.

The belief is too that the number of universes is infinite.[14]

‘Fictional’ multiverses

The concept of the multiverse figures prominently in many ‘science fiction and fantasy novels’.

For some it serves primarily as a plot device, a means to put characters into an unfamiliar situation, or a framework that usually lies in the background for continuity purposes.

For others it is a major theme and focus of the work. It is sometimes used as the basis for exploring “what if” scenarios, such as in alternate history stories. The TV show Sliders from the 1990’s first popularized the concept through the TV entertainment medium.

The film The One (2002) starring Jet Li carried the same idea to the action film medium. The popular MYST computer game franchise uses concepts of describing a world and then linking to that world, which is part of a multiverse of infinite possible and concurrently existing universes, matching the descriptions.

Also, the computer game Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver and its sequels feature two distinct parallel universes.

The protagonist, Raziel, is capable of existing in both the Material Realm, or normal reality, and the Spectral Realm, a dark and distorted version of the former with its own physics and properties.

The Michael Crichton novel Timeline featured a method for what appeared to be time travel by traveling to parallel universes that are identical except for the moment of their birth, thus rendering off-set yet parallel time.

The DC Universe, famous home of Batman and Superman, uses the multiverse as the basis for their universe. This is in part to help deal with their 67 year history, beginning in The Flash issue #123.

In the 1980s DC published the ever popular Crisis on Infinite Earths which detailed a breakdown of the Multiverse at the hands of the Anti-Monitor.

The television series Star Trek has many times gone into parallel “Mirror” universes, and Stargate SG-1 has postulated parallel universes. The Anime series Bokurano is based on a multiverse. In the BBC television show Doctor Who, the Doctor travels between parallel universes and is parted indefinitely from his companion Rose Tyler when she becomes trapped within one.

The fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman is set in multiple parallel universes.

Notes

- James, William, The Will to Believe, 1895; and earlier in 1895, as cited in OED’s new 2003 entry for “multiverse”: “1895 W. JAMES in Internat. Jrnl. Ethics 6 10 Visible nature is all plasticity and indifference, a multiverse, as one might call it, and not a universe.”

- Tegmark, Max (May 2003). “Parallel Universes”. Scientific American.

- Tegmark, Max (January 23 2003). Parallel Universes. Retrieved on 2006-02-07. (PDF).

- Ellis, George F.R.; U. Kirchner, W.R. Stoeger (2004). “Multiverses and physical cosmology“. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 347: 921-936. Retrieved on 2007-01-09.

- Breitbart.com, Parallel universes exist – study, Sept 23 2007

- Merali, Zeeya (2007-09-21), “Parallel universes make quantum sense“, New Scientist (no. 2622), <http://space.newscientist.com/article/mg19526223.700-parallel-universes-make-quantum-sense.html>. Retrieved on 20 October 2007 (Summary only).

- Tegmark, Max, The Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: Many Worlds or Many Words?, 1998. To quote: “What Everett does NOT postulate: “At certain magic instances, the world undergoes some sort of metaphysical ‘split’ into two branches that subsequently never interact.” This is not only a misrepresentation of the MWI, but also inconsistent with the Everett postulate, since the subsequent time evolution could in principle make the two terms…interfere. According to the MWI, there is, was and always will be only one wavefunction, and only decoherence calculations, not postulates, can tell us when it is a good approximation to treat two terms as non-interacting.”

- Deutsch, David, David Deutsch’s Many Worlds, Frontiers, 1998.

- http://www.elfis.net/phorum/read.php?f=3&i=22&t=22

- http://www.iscid.org/papers/Dembski_ChanceGaps_012002.pdf

- Lewis, David (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Basil Blackwell.

- Deutsch, Harry, “Relative Identity”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer ’02), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Paul B. Kantor “The Interpretation of Cultures and Possible Worlds”, 1 October 2002

- Carl Sagan, Placido P D’Souza (1980s). Hindu cosmology’s time-scale for the universe is in consonance with modern science.; Dick Teresi (2002). Lost Discoveries : The Ancient Roots of Modern Science – from the Babylonians to the Maya.

Multiverso

del Sitio Web Wikipedia

Multiverso es un término usado para describir a un hipotético grupo de todos los universos y/o dimensiones posibles; generalmente usado en la ciencia ficción, aunque también como consecuencia de algunas teorías científicas, para describir a un grupo de universos que están relacionados (universos paralelos).

La idea de que el universo que se puede observar es solo una parte de la realidad física dio luz a la definición del concepto “multiverso”.

Historia y descripción

El término “multiverso” se inventó en diciembre de 1960, por Andy Nimmo, aquel entonces vice-director de la British Interplanetary Society de Escocia cuando dio un discurso para dicha organización acerca de la interpretación “varios-mundos” de la física cuántica que se había publicado en 1957.

La definición original de “multiverso” era:

“un universo aparente, una multiplicidad de que, se combina para ser el universo entero.”

A partir de este discurso, la palabra se usó correcta e incorrectamente por unos años en varias instancias en grupos científicos y de ciencia ficción.

En los años 60, el autor de ciencia ficción, Michael Moorcock, interpretó la palabra en una novela. Gracias a nuevas interpretaciones populares basadas en esta obra, la palabra se usa en varios contextos y, se podría decir, con un “multiverso” de definiciones.

Las evidencias científicas que postulan su posible existencia son hoy en día un argumento muy usado para desbaratar la hipótesis del diseño inteligente, y una nueva historia dentro de la cosmogonía.

El Multiverso en la ciencia

Aunque el multiverso principalmente muy usado en la ciencia ficción, actualmente la propuesta de la posible existencia de un multiverso igualmente se ha originado como una consecuencia de teorías físicas elaboradas, como la teoría de las cuerdas; en la que se desea llegar a obtener una teoría del todo que explique el universo.

by M.R. Franks

2003

from ManyUniverses Website

What are Parallel Universes?

Recent discoveries in quantum physics (the study of the physics of sub-atomic particles) and in cosmology (the branch of astronomy and astrophysics that deals with the universe taken as a whole) shed new light on how mind interacts with matter.

These discoveries compel acceptance of the idea that there is far more than just one universe and that we constantly interact with many of these “hidden” universes.

What is needed is a resource that explains in understandable, non-mathematical terms everything from the big bang hypothesis to morphogenetic fields to Bell’s Theorem to the Aspect experiment.

Such a resource now exists.

The Universe and Multiple Realities

“There is no one reality. Each of us lives in a separate universe. That’s not speaking metaphorically. This is the hypothesis of the stark nature of reality suggested by recent developments in quantum physics. Reality in a dynamic universe is non-objective. Consciousness is the only reality.”

With those words, M.R. Franks, a life member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, a member of that organization since high school, and also a law professor, begins his new book, The Universe and Multiple Reality.

- But what is multiple reality?

- How do parallel universes interconnect?

- What are the exact processes by which mind interacts with matter at the quantum level?

Unfortunately, most books on parallel universes and quantum cosmology are written in language that an ordinary intelligent person cannot understand.

Discover the fascinating nature of the universe in which we live and the exact processes by which mind interacts with matter at the quantum level.

Understand parallel universes, multiple reality, and the hypotheses advanced by scientists such as Hugh Everett, Bryce DeWitt, David Deutsch and others.

The Universe and Multiple Reality presents an understandable view of parallel universes and quantum physics––and explains what this means in our daily lives.

The Universe and Multiple Reality explains to the non-scientist reader in understandable, non-mathematical language the paradox of Schrödinger’s Cat, the two-slit experiment, and recent developments in quantum physics and cosmology.

There are a great many other books on “parallel universes,” on quantum physics and multiple reality––but none that offers an understandable model of how minds interact with multiple realities at the quantum level to produce palpable physical effects including paranormal phenomena.

CHAPTER ONE

Postulate One

Every conceivable energy state exists

There is no one reality. Each of us lives in a separate universe. That’s not speaking metaphorically.

This is the hypothesis of the stark nature of reality suggested by recent developments in quantum physics. Reality in a dynamic universe is non-objective. Consciousness is the only reality.

The purpose of this short book is to suggest a model for quantum superposition of realities, the better to visualize how these quantum effects “leak out” into the macroworld and indeed define it.

This first postulate simply asks us to assume that every possible arrangement of matter and energy consistent with the laws of quantum physics exists. This postulate asks us to assume, among other things, that a universe exists “right now” somewhere that differs from our own only in that one electron on one remote planet of one distant star in, say, the Andromeda Galaxy is in a less excited energy state.

Another universe exists that differs from the present universe only in that one photon, of all the photons in the room where this book is being read, is positioned exactly one Ångström unit to the left. Another universe exists in which the earth has two natural moons.

Another universe exists in which there is no planet earth. Another exists in which Elizabeth Taylor has brown eyes. Another exists in which George Washington has a wart on his nose.

If a universe can be imagined, it exists.

The late Sir James Jeans, the great British astronomer, was among the first scientists to recognize the universe as a creature of imagination.

He wrote in 1932:

To-day there is a wide measure of agreement, which on the physical side of science approaches almost to unanimity, that the stream of knowledge is heading towards a non-mechanical reality; the universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine.

Mind no longer appears as an accidental intruder into the realm of matter; we are beginning to suspect that we ought rather to hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter – not of course our individual minds, but the mind in which the atoms out of which our individual minds have grown exist as thoughts.

This new knowledge compels us to revise our hasty first impression that we had stumbled into a universe which either did not concern itself with life or was actively hostile to life.1

Indeed, every conceivable arrangement of matter and energy, however improbable, is postulated to exist as a separate universe.

These universes are, however, static––not dynamic. Dynamic concepts of energy and of motion and of time and of change with time have not yet been introduced into this discussion.

While every conceivable arrangement of quarks, gluons, subatomic particles, atoms, molecules, photons and energy that could possibly be imagined is assumed to exist, this first postulate asks us only to assume that each such arrangement exists in a frozen state for all eternity.

Each of these imagined universes is eternally like an ice palace or like a still frame in a reel of motion picture footage. The frame exists forever simply because it is capable of being imagined, and because nature abhors a vacuum.

This suggestion is not entirely strange to quantum cosmology. Hugh Everett first postulated “parallel universes” in 1957.

David Deutsch, a research fellow at the Department of Astrophysics, Oxford, and a professor at the University of Texas, tells us:

I think it’s safe to say that there is a very large, probably infinite, number of these universes. Many of them are very different from ours, but some of them differ only in some minute detail like the position of a book on a table, and are identical in every other respect.2

Davies and Brown tell us:

If the many-universes theory were correct, however, the seemingly contrived organization of the cosmos would be no mystery. We could safely assume that all possible arrangements of matter and energy are represented somewhere among the infinite ensemble of universes.

Only in a minute proportion of the total would things be arranged so precisely that living organisms, hence observers, arise. Consequently, it is only that very atypical fraction that ever get observed. In short, our universe is remarkable because we have selected it by our own existence!3

Notice, however, that while Everett, DeWitt, Deutsch and others postulate an infinity of universes, each of their postulated universes is dynamic, moving, changing.

Bryce DeWitt of the University of Texas tells us that under this theory,

“every quantum transition taking place on every star, in every galaxy, in every remote corner of the universe is splitting our local world into myriads of copies of itself. Here is schizophrenia with a vengeance!”

There can be no doubt that these pioneers envision multiple worlds that are dynamic, moving and changing.

P.C.W. Davies and J.R. Brown speak of the imaginary experiment involving Schrödinger’s cat, so named for the physicist Erwin Schrödinger who first conjured up the idea in 1935. In this thought experiment a cat is placed in a box.

A quantum event determines whether this imaginary cat is poisoned or not. Perhaps a Geiger counter is arranged to count the number of particles encountered in a defined time period, and if the count is odd, a hammer is tripped and a glass vial’s deadly contents are inflicted on the cat. If the count is even, the cat is allowed to live.

However the situation may be arranged, it is arranged so that a quantum event determines the cat’s fate.

Quantum physics tells us that upon the happening of the event the cat goes into two superimposed states, one of being half alive and the other of being half dead. Only when the human experimenter arrives later to look into the box does objective reality “collapse” in upon the events.

And then that reality instantly collapses back retroactively to the time of the fateful event.

Speaking of this, Davies and Brown tell us:

According to Everett the transition occurs because the universe splits into two copies, one containing a live cat and the other a dead cat. Both universes contain one copy of the experimenter too, each of whom thinks he is unique. In general, if a quantum system is in a superposition of, say, n quantum states, then, on measurement, the universe will split into n copies.

In most cases, n is infinite. Hence we must accept that there are actually an infinity of ‘parallel worlds’ co-existing alongside the one we see at any instant. Moreover, there are an infinity of individuals, more or less identical with each of us, inhabiting these worlds. It is a bizarre thought.4

In Everett’s view, because each of these worlds is dynamic, the live cat goes on living in the one world, while in the other world someone presumably takes the carcass out of the box and buries it.

David Deutsch tells us that Everett’s universes all are “changing in content.”5

The present postulate differs from their thinking in that here each of the postulated universes is absolutely static, frozen, unchanging.

CHAPTER FOOTNOTES

- Sir James Jeans, The Mysterious Universe (New Revised ed.), New York: The Macmillan Company, 1932; Cambridge: The University Press, 1932), p. 186.

- David Deutsch in The Ghost in the Atom, ed. P. C. W. Davies and J. R. Brown (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 85.

- P. C. W. Davies and J. R. Brown, ed., The Ghost in the Atom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 38.

- Ibid., at 35-36. (Emphasis added.)

- David Deutsch in The Ghost in the Atom, ed. P. C. W. Davies and J. R. Brown (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 86.

A Scientific Explanation for the Paranormal

The Universe and Multiple Reality

“There is no one reality.Each of us lives in a separate universe. That’s not speaking metaphorically.

This is the hypothesis of the stark nature of reality suggested by recent developments in quantum physics. Reality in a dynamic universe is non-objective.

Consciousness is the only reality.”

With those words, M.R. Franks, a life member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada who has belonged to that organization since high school, begins his new book, The Universe and Multiple Reality.

What is multiple reality?

How do parallel universes interconnect?

What are the exact processes by which mind interacts with matter at the quantum level?

Those are the questions that Franks, a law professor, tackles in his book as he explains the physics of miracles and of paranormal phenomena such as ESP and telepathy.

Franks explains that recent discoveries in quantum physics (the study of the physics of sub-atomic particles) and in cosmology (the branch of astronomy and astrophysics that deals with the universe taken as a whole) shed new light on how mind interacts with matter.

These discoveries compel acceptance of the idea that there is far more than just one universe and that we constantly interact with many of these “hidden” universes.

Professor Franks says he feels it is unfortunate that most books on parallel universes and quantum cosmology are written in language that an ordinary intelligent person cannot understand.

What he felt was needed is an understandable, non-mathematical source that explains the concept of parallel universes and its relationship to perceived reality—a source that brings together the contributions of such greats as David Deutsch, Albert Einstein, Hugh Everett, Stephen Hawking, and John Wheeler.

“I wanted to fill the need,” the author says, “for an understandable source that makes clear the concept of parallel universes, multiple reality, and the nature of the multiverse or superuniverse.

We talk about miracles, time travel, faith healing, and mental telepathy and how the latest scientific discoveries explain how these phenomena work.”

Franks promises that The Universe and Multiple Reality will enable the average intelligent reader to understand parallel universes, multiple reality, and the latest hypotheses advanced by scientists. It will also give insight into the paranormal and the miraculous.

The author claims that just about anyone can easily learn the nature of the universe in which we live and the exact processes by which mind interacts with matter at the quantum level.

The theory also explains the mechanics of faith healing, the power of prayer, and even witchcraft and voodoo.

“I have presented a view, understandable to the non-scientist reader, of parallel universes and the latest developments in quantum physics—and I explain what this means in our daily lives,” says the author.

“TheUniverse and Multiple Realitybreaks new ground. There are a great many books on parallel universes, on quantum physics and multiple reality—but none that proffers an understandable theory on how the human mind interacts with multiple realities at the quantum level to produce palpable physical effects,” claims Professor Franks.

The author feels this book is a must for any intelligent person curious about the place their mind holds in the cosmic scheme of things.

Hear Professor M. R. Franks

Beyond the Ordinary is a program originating from Radio Station KRSE in Washington and heard worldwide via the Internet.

On 25 March 2004, and invited back many times, most recently on 3 February 2006, hosts Nancy Lorenz and Elena Young interviewed the author, Professor M. R. Franks, devoting a full hour each time to his groundbreaking book, The Universe and Multiple Reality.

The fourth interview, conducted on 22 November 2004, was on the forty-first anniversary of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. The subject of that one interview was the assassinations of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

All other interviews are on the subject of parallel universes and multiple reality.

- To hear the first interview (multiple reality)

- To hear the second interview (multiple reality)

- To hear the third interview (multiple reality)

- To hear the fourth interview (JFK/MLK assassinations)

- To hear the fifth interview (multiple reality)